Critically Engaging with Cultural Productions

Cinematic and Literary Modes of Historical Inquiry

The following is the adapted transcript of a talk I gave for a Filipino/x-American history conference. I was joined virtually by my tito (whom I will henceforth refer to as TJ), a filmmaker and composer based in the Philippines. Please note that not everything I or my tito said that is written here will be representative of each other’s paradigm. We are two individuals with distinct geopolitical positionalities having a good ol’ exploratory dialogue, after all.

Thank you to my tito for making time for this talk in spite of a demanding film schedule. Thank you to the artists and cultural workers who hosted us in their museum space. Thank you to my loved ones who attended the talk and cheered me on in my nervousness. And thank you, kanto readers, for your critical engagement.

Sites of Interwovenness

Introduction given by me

Tonight’s theme is “Woven Together”— TJ and I are attempting to be “woven together” in a few different ways that are continually in flux and not mutually exclusive:

The first site of interwoven-ness that TJ and I are occupying (and perhaps the most apparent one based on the hybrid format of this talk) is place. I’m part of a global Filipino population. More specifically, I was born in Mindanao before immigrating to the U.S. with my parents. TJ, however, has been living in the Philippines and has only visited the States once. I haven’t been back to the Philippines since my parents and I immigrated here over two decades ago.

The second site concerns our creative practice. TJ has a filmmaker and composer’s background, while my educational background is in literary studies and the behavioral sciences. His career is storytelling, and my time as an undergraduate student was consumed with reading these stories. At the same time, TJ is an avid reader, and I too am venturing into producing my own scholarly and creative works.

The third and final site is our historical perspective. What you’re going to see from TJ is a broad reckoning with the creative possibilities of accounting for larger-scale historical Filipino migrations. For my portion, I’m going to take a bit more of a zoomed-in approach and talk specifically about our own family history.

Hopefully what emerges from this collaboration across these three different sites are tempered, yet optimistic considerations.

Dramatizing the Cultural Past on Screen

Asynchronous talk by TJ

I'm a filmmaker based in the Philippines and have been creating feature-length movies since 2007. I'm not Filipino-American, so my work and its impact are centered on the Philippines. I do have relatives in the US though, including my co-presenter. I work on films across various genres, but the ones most relevant to this talk are historical biopics: Heneral Luna (2015) and Goyo: Ang Batang Heneral (2018). These films, part of an ongoing trilogy with the final installment focusing on President Manuel Quezon, explore significant themes in Filipino history.

Today, I want to explore the potential of shared storytelling between Filipinos of the diaspora and those of us who remain in the Philippines. I'm fascinated by our history beyond wartime, by the nuances, conflicts, and struggles inherent in migration stories. These narratives, where our paths both converge and diverge, are rich with possibilities. To set the stage, let me provide some context on Heneral Luna and Goyo.

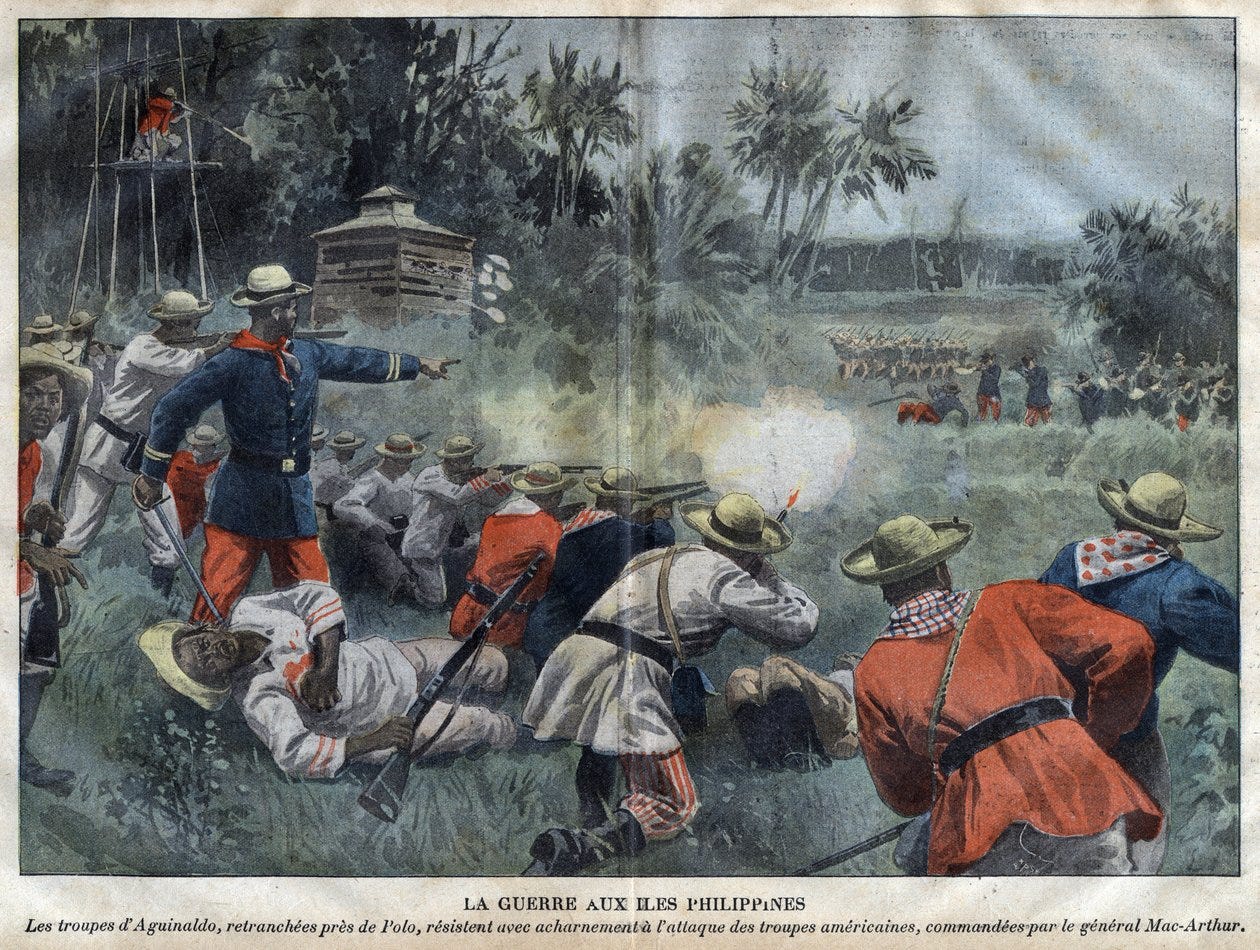

Both Heneral Luna and Goyo are set during the Philippine-American War and are attempts to dissect the concept of “bayani” or hero. The goal was to reveal the human side of what were essentially statues on a pedestal. The majority of Filipinos don't really have a deep appreciation of history apart from celebrating holidays and paying lip service to vaguely defined notions of revolution and freedom, so the films tried to engage the audience in conversations about history, how things have or have not changed since 1899, and to provide a closer look at figures who have become stagnant in history books. The films also dramatize how Filipinos almost achieved freedom from Spain, only to lose it to the Americans.

Heneral Luna explores regionalism, highlighting how a Filipino's allegiance extended only to their province rather than the nation. Considering how we are separated by islands and hundreds of languages, how we were colonized by Spain before we had an imagined national identity, this narrow allegiance made complete sense. Pockets of resistance against Spanish abuses existed throughout Spain's 300-year rule, but freedom only started becoming more tangible for Filipinos in the late 19th century when Spain's status as a global power weakened, and upper middle class Filipinos learned about enlightenment values after studying in Europe. Yet, in the middle of this fight for freedom, we fought among ourselves. Cavitenos versus Ilocanos versus Tagalogs versus Ilonggos and so on. We had a common enemy, but the interpersonal connections were shallow, and the aspirations of freedom clashed with personal power struggles.

Meanwhile, Goyo tackled themes of idolatry, contrasting allegiance to an imagined nation with blind loyalty to a leader. While the country was fighting for its freedom and national identity, Goyo was also struggling to find his identity as a citizen, rather than just a follower of President Emilio Aguinaldo. Filipino culture puts great emphasis on its celebrities and pop icons, its public figures, its religious leaders and cult leaders. While we shouldn't devalue the human need to have someone to look up to, I believe this need should always be paired with a healthy dose of skepticism and critical thinking. Unfortunately, the illustrados who introduced Western enlightenment values didn't or couldn't effectively integrate these ideas into the broader population. Additionally, the American education system that followed did not prioritize critical thinking skills, leaving a gap in our cultural and intellectual development.

We have skilled laborers, technicians, talented artists, everything necessary to sustain an economic system allied with foreign interests, but the capacity to question our beliefs, to criticize the people we follow, to be cognizant of our arc in history, to think about thinking—, all of these never really mattered as much, and has largely remained an academic pursuit or an upper-middle class to upper class endeavor. So Filipinos largely remain untethered to their roots. If Filipino-Americans feel a need to reconnect their roots, I'm willing to bet Filipinos need that even more.

The public discourse for the two films was largely positive, but they went in all directions. Heneral Luna became a pop culture phenomenon despite criticisms of promoting strongman authoritarianism and influencing the 2016 national elections. Goyo meanwhile incited the ire of at least one government official, who was upset that the film depicted Filipino soldiers deserting their posts and fleeing like cowards after Goyo's death at the Battle of Tirad Pass. The official was so incensed, he called for government approval of screenplays. Thankfully, that never materialized, but the depiction of soldiers fleeing after their leader's death was a key point of the film, that some of us have shallow allegiances. And accounts of cowardice and desertion do exist in historical records. We were kind of placed in an awkward position where a fictional medium, i.e., film, tries to be truthful while a government official wants to maintain the fiction. It's funny stuff. These public conversations, whether serious or silly, are what we need more of.

The Filipino-American experience is, of course, different. The concerns of Filipino immigrants likely focus on surviving and thriving as minorities in foreign lands. And I assume that the need to reconnect to one’s roots after settling in the US is also crucial, though I won't presume to know all of its nuances.

There's so much potential in the space that Filipino-Americans and Filipinos share— stories of journeys, connections lost and regained, survival and resilience, and defining home… Try to imagine dramatizing the stories of Filipinos who rode the Spanish galleons and deserted their posts to settle in Mexico from the 1500s to the 1800s. Consider the widespread romance between Filipino men and white women in California in the early 1900s that caused racial tension, where Filipinos were characterized as having a “pathological attraction to white women that could not be contained by conventional modes of enforcement.” The idea of white men being threatened by Filipino rizz is funny [see the TikTok above that I, Ysampagita, inserted], especially if you consider that over here it's kind of the opposite because there's still a sizable chunk of Filipino women preferring Caucasian men or AFAMs [“a foreigner around Manila”] over Filipinos.

In contrast, imagine the mysterious Filipino colony in the bayous of the Mississippi River established in the 1700s where no women lived, and the one time a beautiful woman entered the village, bloodshed ensued. Their solution to maintain peace and order was to cut up the woman to pieces and feed her to the alligators, which was absolutely nuts.

There are also meaningful stories from the lives of Filipinos who worked in the plantations in Hawaii in the early 1900s. Imagine the conflicts and struggles of coexisting with a Japanese population, along with native Hawaiians. Then we have stories of Filipino whalers in Alaska, the soldiers who joined the Civil War and World War I.

A lot of these are stories of the working class, of Filipinos looking for a better life outside their country, stories of leaving and uprooting. As a filmmaker, I would love to see films being made about their lives. As an audience member, I would be thrilled to watch them. Granted that making period films is expensive, but if there's one advantage the Philippines has over America, it's that making movies here is very cheap. According to some accounts, Goyo was the most expensive film ever produced in the Philippines, and that only amounted to less than $2 million US dollars.

My point is that there are so many questions about our past that would be great to see dramatized on screen. But we have to move past nostalgia to a more vivid engagement with history. We have to ask trickier questions about these stories of leaving and staying. For example, at what point does the Filipino migrant's lineage become more Western than Southeast Asian? How many generations does it take? What are the limitations of reconnecting to one's Filipino roots? Or is there anything like a Filipino essence to reconnect to in the first place beyond superficialities? On the other hand, what’s behind the tendency of Philippine media to keep celebrating the achievements of half Filipinos living overseas? These are tricky questions, but as a storyteller based in the Philippines, I find them important because, despite the histories of America and the Philippines being intertwined for better or worse, we have to be aware when we're applying Western constructs in our stories. Some of them are helpful, but it's possible that some of them may be harmful. As a consumer of pop culture, however, it would be an amazing experience to have these conflicts play out in stories of the diaspora. We don't need to have answers on screen. It's the asking that matters.

Discussing our past is crucial for identity formation. While the concerns of Filipinos and Filipino-Americans differ, the intersections of our experiences offer opportunities for cultural enrichment. Embracing both our shared and divergent histories can help us build stronger connections, particularly through the medium of pop culture.

For the longest time, Filipinos have been connected by their consumption of entertainment. This cultural currency has value, but much of it is fleeting. Imagine a cultural currency that transcends Western constructs and celebrates Filipino identity on its own terms. For a people divided by geography and language, developing a cohesive identity that incorporates time— meaning lineage, legacy, and roots— is vital. This cohesion helps us define our place in history and make informed decisions as individuals and communities. In an increasingly fragmented world, fostering stronger, more defined connections would be wonderful.

Writing through Family History

Talk given by me

I was 14 years old when I saw Heneral Luna (2015) in American theaters, and I didn’t quite have a sense for how historical that moment was. Heneral Luna is now the highest-grossing historical film in Philippine cinema, and that’s a testament to how potent and resonant this historical inquiry via pop culture can be.

Since TJ discussed popular representation in cinema, I’m going to focus more so on personal histories, or as I like to think of it— history with a lowercase H as opposed to Filipino/x-American capital-H History.

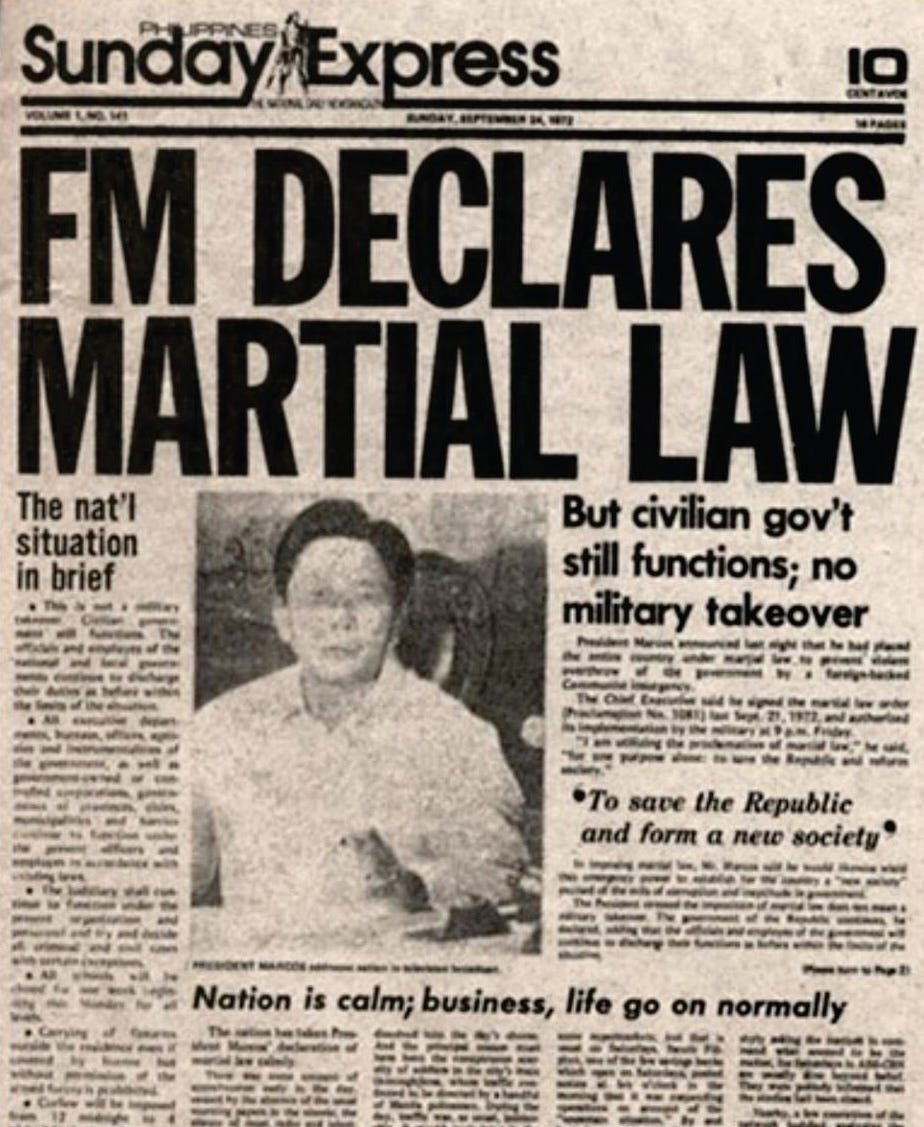

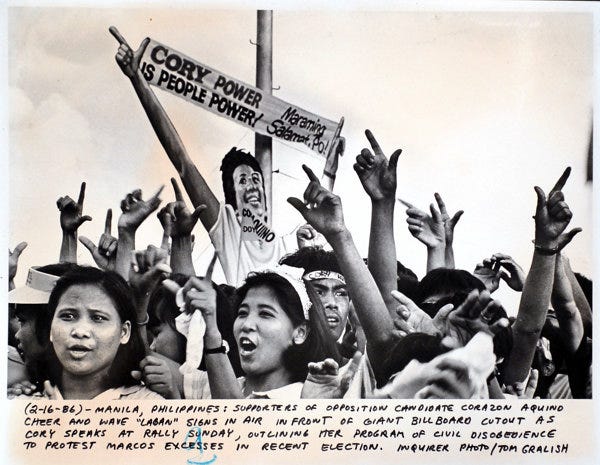

I’ll begin almost forty years ago in the Philippines, when over two million Filipinos mobilized on Epifanio de los Santos Avenue to oust Ferdinand Marcos after two decades of martial law. This series of mass protests would be known as the first EDSA revolution (yes, there was a second one), after the street in Metro Manila. You may also have heard it referred to as the People Power Revolution. The Ls the people are holding up in the picture above stand for laban, or “fight,” as well as an abbreviation for “Lakas ng Bayan (Power of the People,” a coalition organized by political opposition Senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. who criticized the Marcos regime and was assassinated at Manila International Airport. Among the thousands of protesters present during the EDSA Revolution were my lolas, one of whom I was named after.

Years later on the anniversary of the EDSA I Revolution, I was born in the Philippines. I could share this information with you all and claim that I come from a line of Pinay advocates and dissenters. “I am of the generation that ousted Marcos Sr.” It’s a really romanticized way of framing things. And I don’t say that to discount my lolas’ participation in popular resistance, but to be mindful of the way I’m tinting their experience that may flatten the shifting gradations of truth within our ongoing family history. Therein lies the crux of this conversation that TJ and I are attempting to have in front of an audience— how do we discuss our collective past? What could this critical engagement with our histories look like in our daily lives? Or in Filipino-American writer Elaine Castillo’s words, “What if art was the space ... for us to encounter our bondages— and our bondedness?” These sound like very lofty questions, which they are, but as Castillo wrote in her book of essays How to Read Now (2022), “This work has left a will, and we are all of us named in it: the inheritances therein belong to every reader [...] So too the world we get to make from it.” In the spirit of that, I’m going to walk through a processual account of what investigating my historical inheritance has looked like for me over the years.

I was a 6th-grade student in rural Louisiana when I somehow got looped into a social studies project with one of the only other Filipino kids I knew. He was a year older than me, and his nanay would often babysit my little sister and I while our parents were working. I have barely any recollection of the actual content of that presentation, but I know we had a tri-fold poster board with a Filipino flag painted on the back. Neither he nor I were very confident explaining our project because honestly, his mom did the heavy lifting with research and putting the poster together. That was the first instance I learned of a major Philippine historical event, even if my actual knowledge was lacking in depth.

Fast forward to my second year in college, I took an English class on Southeast Asian Literature, and it was taught by the only Filipino professor I’ve had. It was the first time I got to read extensively about martial law, even though I had heard about it from that 6th grade social studies project and eventually, my lolas. It was also the first time I had read novels about Filipino people that were authored by Filipino people. Among the texts included in the syllabus were State of War (1988) by Ninotchka Rosca, Gun Dealers’ Daughter (2010) by Gina Apostol, Dogeaters (1990) by Jessica Hagedorn, and the indie film Remittance (2015). I think then it really clicked that our cultural productions have existed for a while, even if I was woefully unaware of it for a long time. Having grown up in the deep South for over a decade, I was the only Asian girl in my class (and I don’t mean in a single classroom, I mean for my entire cohort year), and it was only in college that I learned how to recognize and name things like colonial mentality, internalized racism, Eurocentricity.

My fourth and final year of college, I was starting to write a pitch for a thesis topic. With the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement popular resurgence and the pitfalls of Instagram activism, it was quite easy to become disillusioned with the idea of creating a new world. Progress is slow, and there are always fires to put out. Under the guidance of my thesis advisor, I decided to write through that discomfort in a collection of essays that focus on diasporic Pinay poetry and also personal anecdotes. I’ll read the opening lines from the manuscript, entitled A Path is Formed by Walking:

“This work has layers of sediment, formed from guerilla deposits of lived realities that accumulated, then eroded, returned unrecognizable, and solidified somewhere along the way. The works of diasporic Pinay poets are a mosaic, voicing a transnational Philippine consciousness of dissent in English. This written culture of protest is rooted in a radical hope for the futures of Filipino people. We world-weary, borderline-if-not-already-nihilistic youth may be less inclined to recognize the underlying hope not just in Pinay poets’ work, but all around us. This anticipation of a worsening political climate and subsequent disavowal of class struggle spurs a reimagining of the political structures forcing nearly 5,000 Filipinos into diaspora every day. By writing through (i) personal stories obscured by generational shame and cultural stigma, and (ii) poetry, a genre generally overlooked by formal literary criticism in favor of Philippine prose works, I resurface joyful tales viewed as peripheral to our stories of suffering. In a similar way to Pinay poets’ reworking of English, a colonially-enforced language, our generation of youth must sharpen our political focus in order to subvert the imperialist histories we have inherited. In sharpening our political focus, we may commit to an ongoing struggle of rallying a fragmented nation and our people’s own searching spirits.”

Like TJ said earlier, the important thing is the asking. It’s an ongoing practice, and that means we must commit to constantly reorienting and remolding ourselves. These days, the process looks a little different from me. I graduated college last year, and I’m not currently in graduate school (more on that in an upcoming post…). I’m working full-time now, so I’m pursuing these historical inquiries largely outside of my 8 to 5.

Late last year, I started a Substack called kanto (I had just broken up with my then-boyfriend, so it seemed like as good a time as ever to start). (As my subscribers know,) I publish essays about dissenting from the ideological regimes of capitalist imperialism, patriarchy, and racism (a node called “Disturbing the Sediment”). I also publish review summaries of recent books I read, which tend to be non-fiction and essay collections, (this node is called “Thinking in Marginalia”). Lastly, I maintain an archive of some of the pieces I wrote as a college student (pretty intuitively named “The Undergraduate Archive”) as a reminder of where I’ve been in piecing my politic together in relation to where I stand now. Some of the coolest things to emerge from this project so far is having essays reposted by Dr. Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales (credited with developing Pinayist theory and who, by the way, followed my Instagram, AH) and Barbara Jane Reyes (a prolific Pinay poet from the San Francisco Bay Area and one of my favorite. poets. ever).

Now that I’ve gone through a condensed timeline of my deepening understanding of personal histories, I want to offer some practical recommendations:

Seek out one another, especially beyond this conference setting. There’s this Bretman Rock quote that I love, where he is talking about growing up watching the Filipino Channel his skepticism of people who say they’ve never seen people who look like themselves on TV; Bretman shook his head and said, “Girl, change the channel, duh. The hell?” That just goes to say we’re here, we’ve been here, you’ve just got to look in the right places.

Be curious about one another. Ask questions, strike up conversation. What do we not know? Consider presence and non-presence in your life. What were we taught growing up? Why were we taught in that way? Ask your family, or look into local Filipino histories. I know that the Woodson Archive in the Rice University library has materials from FANHS.

Be invested in your community. Join a Pinoy organization, and work to enrich the collective life of the local Filipino population. I’ve gotten to document some events by local Pinoy organizations like a plant workshop/exchange and an arts showcase. Some of my pieces are also featured in a publication written by and for queer Filipino/x-Americans. [There was an open call for submissions posted by a Filipina-run indie press last fall, so if you ever see those announcements floating around, respond! Send something of yours in.] These have been beautiful things to be a part of.

To end, I’d like to share something a cultural worker from the Philippines said during a recent artist talk I moderated— there is no higher creative practice than shaping the world. That is the power of our art and cultural productions in a nutshell. Whether you are an accomplished movie director or just a Fil-Am girl trying to make sense of a hybrid identity, just know that we are all active bearers of history. Thank you.