Woven Filipina Narratives

Figuring a Transnational Asian Feminist Praxis through Pinayist Dialectics

The following is the extended version of a reflection I wrote for a local university symposium roundtable about Asian/-American feminist studies, in which I was one of six panelists. Thank you to my fellow panelists for sharing space and insights; learning and connecting with you has been revitalizing, especially in a time that I have just been in a slump. I’m keeping up with each of your very cool works and am heartened I get to imagine a new world with you.

This panel embodies the necessity of Asian/-American feminist studies having the ideological room to be proliferated by taking stock of discourse across institutions, nation-states, occupations, etc. so as to not flatten or other gradations of difference in ways of knowing.

Asian/-American feminism must be:

dialectical (includes a multitude of devalued subjectivities);

intersectional (internationalist and class-oriented in particular); and

democratic (pro-people in terms of anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, anti-capitalism, anti-racism).

While the site of struggle for Asian/-American feminist studies is the academy, practitioners of Asian/-American feminisms must not lose sight of the end goal to upend violent, oppressive systems of power through a concrete imagination and material strategy rather than to analyze and cope with them within the very ivory walls that delimit our selfhood and would have us disavow our histories.

Today, the thread that I’m pulling on for everyone’s consideration is what started as a theory almost thirty years ago in 1995 proposed by Allyson Tintiangco-Cubales, a professor in the Asian American Studies Department at San Francisco State University. The theory, or praxis (a better term), is called “Pinayism.” A Pinay is a Filipina American, and yet the work of Pinayism, while originally localized to the U.S., does not occlude Filipinos in diaspora. Also, semantically, most people consider Pinay to be synonymous with Filipina. [I asked my mom to make sure, LOL.]

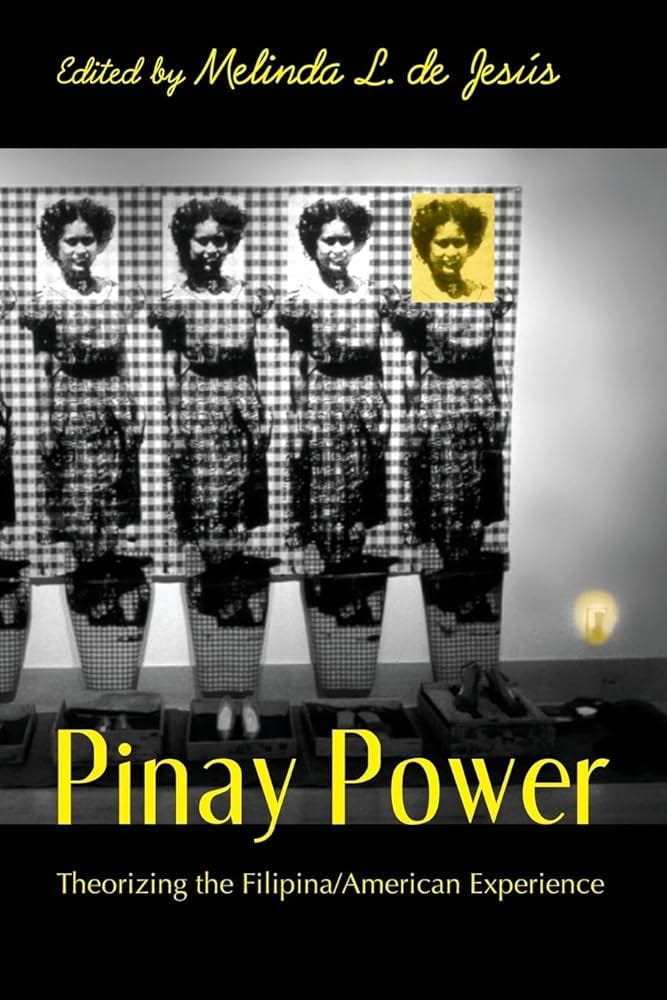

Ten years after Pinayism was coined by Dr. Tintiangco-Cubales, an anthology titled Pinay Power: Peminist Critical Theory/Theorizing the Filipina/American Experience (2005) edited by Melinda L. de Jesús, associate professor and former chair of Diversity Studies at California College of the Arts, was published.

This is a cornerstone text in articulating the Pinayist framework, made up of essays that meditate on identity and decolonization, intimacy and desire, navigating the internet and academia, and making art. One of the essays was written by Dr. Tintiangco-Cubales. In it, she describes Pinayism as seeking

“the intersections where race/ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, spirituality/religion, educational status, age, place of birth, diasporic migration, citizenship, and love cross” with the requirement of “engag[ing] in a discussion… of reevaluation, reconstruction, retransformation, re- transgression, and, especially, relove for one another” (122,128).

Tintiangco-Cubales writes that Pinayism “draws from a potpourri of theories and philosophies, including those that have been silenced and/or suppressed,” but that Pinayism is decidedly not a Filipino-ized feminism (121). We’ve seen the dominance of white liberal feminism dating back to the U.S. suffragette movement and the emergence of womanism, coined in 1983 by Black American writer Alice Walker, as a counter to the marginalization and erasure of Black women's voices and other women of color. As womanism has been deemed the feminism for women of color, a feminist approach that does not establish its situatedness and stakes risks subsuming the specific struggles of other groups and letting invisibilized subjectivities fall through the cracks. We can learn from Black feminist thought and make pointed, concrete analyses of local struggles while emphasizing, insisting upon, their interconnectedness.

Filipino-American psychologist Kevin Nadal quoted a later definition of Pinayism (provided by Tintiangco-Cubales in 2009) in a chapter titled “Filipino American Experiences With Gender and Sexual Orientation” as part of the second edition of his book Filipino American Psychology: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Clinical Practice (2021):

“A process, place, and production that aims to connect the global and local to the personal issues and stories of Pinay struggle, survival, service, sisterhood, and strength. It is an individual and communal process of decolonization, humanization, self-determination, and relationship building, ultimately moving toward liberation” (qtd. in Nadal 119).

Almost 3 years ago, I was working as a research project lead in an Asian-American Medical Humanities lab. [Looking back, it’s wild that I even got the opportunity to do that.] I pursued a project in which I collected oral histories from Pinay nurses about their migration story, the reason being the Philippines has a heavily feminized labor export economy that’s reliant on nurses and domestic workers. I interviewed relatives, my neighbor, and the Philippine Nurses Association of Metro Houston was also kind enough to share my call for participants. I went into the project with the clearcut aims of (i) excavating the U.S.’s imperial past through documenting interviewees’ experiences of being recruited and (ii) challenging the cultural amnesia around why we’re here in the first place, why being uprooted seemed to be the better, if not the only, option for a better future. I asked the participants questions like how they learned about the nursing career pathway in the U.S., what their motivation was for pursuing nursing, if they had relatives who were nurses, what culture shocks and challenges they encountered when they first immigrated to the U.S., and what they miss about the Philippines.

The answers I received went in a direction that I had not anticipated. They are grateful for the kind of living that was made possible in the U.S., even as perpetual foreigners. This was very much a touch-grass moment for me. I learned, what might now seem like an intuitive lesson, but that when it comes to political consciousness, people you may preemptively consider kin and therefore like-minded aren’t going to approach or even name things in the same way you do. I call it “gender-based discrimination”; they call it being a Filipina nurse. I call it “neo-colonialism”; they call it U.S. aid to the Philippines. The challenge of movement-building is to win the hearts and minds of people such that the collective liberatory project is each of ours evenly and also intimately.

Reactionary offense at their “opinion” would put me at odds to them, and only the enemy benefits from that. As Filipino rapper Power Struggle wrote in the lyrics to the song “The Healing,” one of the songs in his EP This MIC Kills Fascists,

“Put the blame on the system and not the people.”

Even though for that project’s conclusion I couldn’t compose this formal postcolonial critique in the way I initially set out to, integrating within my own community was what ended up deepening my praxis. I got schooled in the best way. Knowledge derived from practice, indeed.

I’ve been a community organizer in a mass organization of Filipino/x youth and students for almost four years now, and our annual program is (it has to be) based on community-building. The South’s repressive political environment is no secret, and to respond to those material conditions, a lot of our work has been to first, find one another, and second, raise political consciousness for organized action.

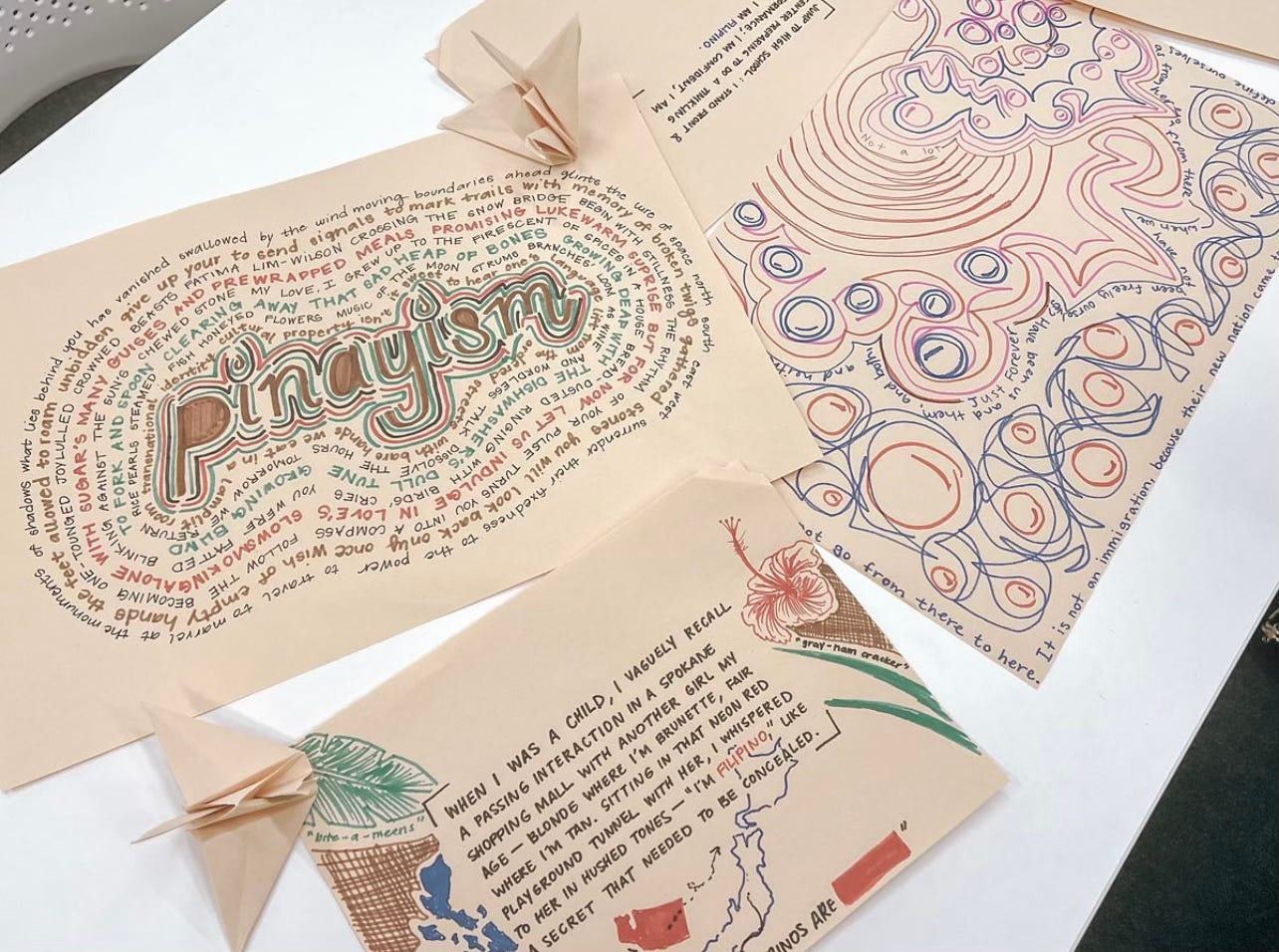

At the end of 2023, we hosted an event about mapping Filipino diaspora. Our three objectives were to: (i) historicize our positionalities in diaspora (our diaspora is a direct result of corruption and imperialism); (ii) draw connections between macro systems of labor export to personal stories of migration (i.e., connecting political to personal); and (iii) empower attendees to take action, as we are all active agents in changing conditions materially.

To do this, we looked at a historical timeline of large waves of Filipino migration and compared it against almost 60 years of the state’s labor export policy. We then shared our family migration stories, our personal reasons for leaving. The event culminated in the creation of a collective art piece (something we’ve been doing for the past few years as an annual tradition), where a global map was printed onto a wood panel, small tags containing our written and/or doodled migration stories were threaded together with different colors of yarn, and they were hammered onto the map with thumbtacks.

I share this specific example of community organizing because it reminded me of something Filipina writer Aida F. Santos wrote in an essay about Marxism and the Philippine women’s movement:

“Feminism offers a reformulation that makes sense of people's daily experience in the intimacy of their lives within the complex hegemonic structures of global oppression” (qtd. in Santos 137).

Since learning about Pinayism, Pinayism has surrounded me. We can identify contradictions and also understand that some things don’t necessarily need to be reconciled in order for something like Pinayism, or Asian/-American feminisms more broadly, to have ideological solidity. I believe in and am willing to fight for a world where truth and beauty abound, where people can think freely and deeply about the kind of lives they want to lead, and they have the means to actualize it. Pinayism is a mode of access for liberatory, feminist praxis in which there are endless, imminent possibilities for community healing and world-building.

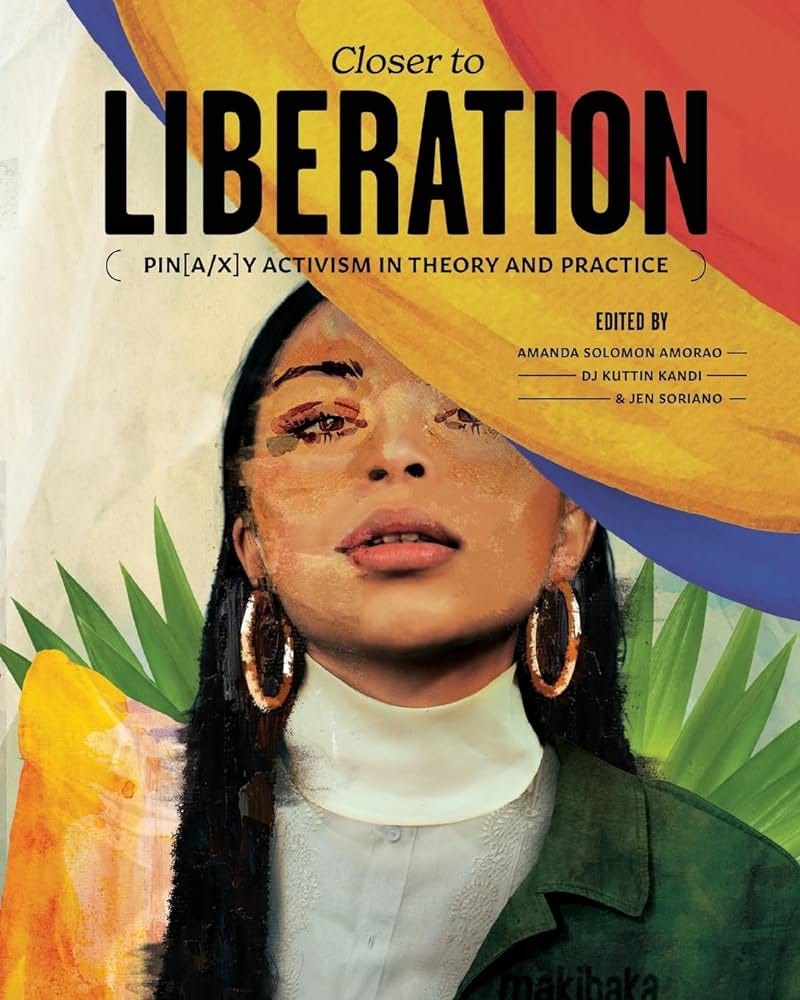

There’s work left for us to do with Pinayist studies. There’s actually a new volume titled Closer to Liberation: Pin[a/x]y Activism in Theory and Practice (2023) edited by Amanda Lee Solomon Amorao, Candice Custodio-Tan, and Jen Soriano that is a continuation of the conversation that Allison Tintiangco-Cubales and Melinda L. de Jesús started. I’m itching to get my hands on it!

In the meantime, I’ll continue sharing my cultural production and doing the community work. I hope that when this panel concludes, you come away with a firm motivation for nurturing Asian/-American feminist studies in the academe and the radical hope in knowing the completion of its tasks are already underway.

It’s been a few weeks since I last posted. Life has been keeping me occupied, and I, at last, found the time to share this more recent work. There are a few other drafts that are just going to have to marinate a little longer before I can publish them.

I wanted to end with this painting from Filipina artist Lydia Velasco. I came across her work as I was searching for thumbnails for today’s post, and I was immediately enamoured by the way she portrays Pinay women in her modernist art. Velasco describes her depiction of the female form as “elongated, massive, heavily set, and invigorated.” In a commentary about Velasco’s pieces on her art blog, Jenny writes that Velasco’s artistic focus on women is “liberating them on her canvases and asserting their glory, identity, and freedom.”