“Someone explained the blues

was a suffering from political despair.

And yet it is hard to fathom art

from the unshielded body.”

(Oliver de la Paz, lines 1-4 of “Diaspora Sonnet as My Father Thinking Aloud About the Wastefulness of Rice Tossed at a Wedding” in The Diaspora Sonnets)

Maybe you don’t consider yourself an avid reader or someone knowledgeable about art, much less literature and poetry, but you’re given materials to read every day through mass media. Presidential election commercials. Pharmaceutical ads. Pop girly music videos. Our reading practices inform the way we interact with the world and each other, so is it not worth bearing in mind? Just thinking can’t be enough; we have to think about our thinking. We have marked stakes in what we read and how we read. Things are tinted, everyone has an agenda, many will try to sell you on something.

If you’re active on social media, maybe your feed is full of video footage of the I“D”F’s carpet bombing and indiscriminate targeting of residents in the Gaza strip (the tent massacre in Rafah in May, the flour massacre in February, the World Central Kitchen workers being killed in an I“D”F strike in April, the fake humanitarian aid trucks used by the I“D”F to carry out a ground invasion of a refugee camp in June—to our collective horror, the list has continued since I started editing this piece over the summer), TikToks of parents and their children begging you not to scroll away and to help them raise the funds to seek refuge, photos of charred, still-developing bodies and scattered remains with seared clothing, torched belongings and birthmarks being clues for identification. Maybe you’re into Law & Order, and you saw the latest season opener, “Freedom of Expression,” which uncritically portrays violence ensuing “as a consequence” of pro-Palestine, anti-war protests on a university campus. [This aired in January of this year, by the way. Leave it to the wealthy, white producers to dictate both-sides-ing and sensationalizing the academe’s complicity in g3n0cide!]

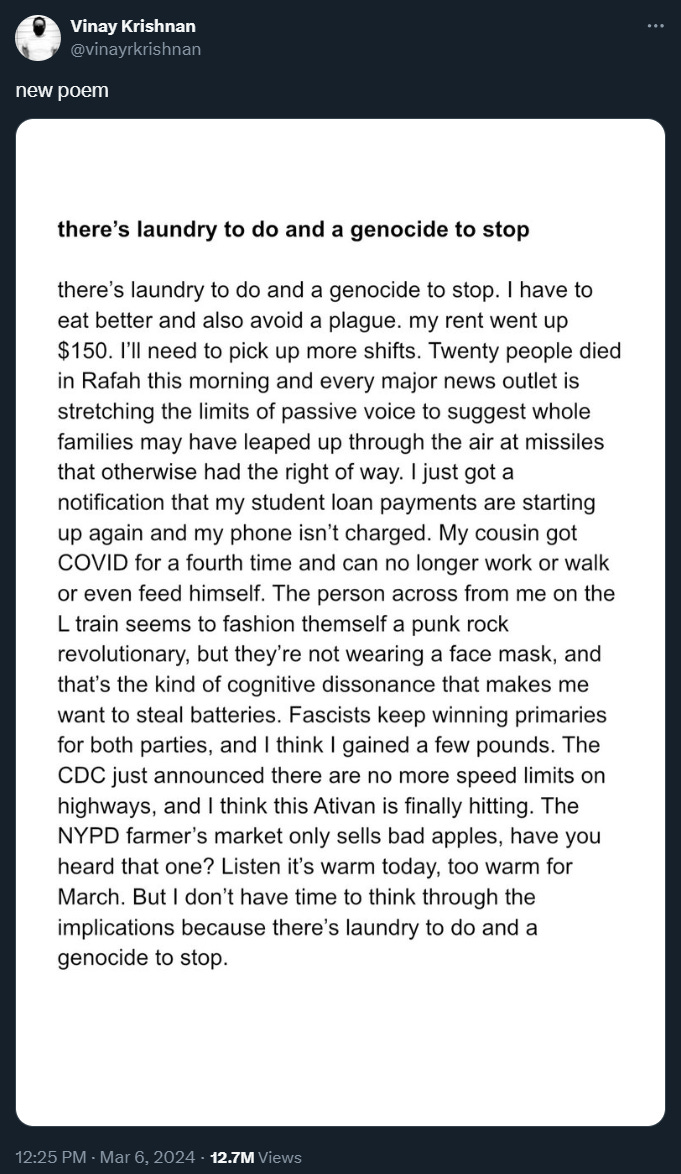

Nothing has made me understand the urgent political stakes of our art and cultural productions like the ongoing historical moment we’re living through. [I wrote part of this essay from the liberated zone set up on my alma mater’s campus (yes, I’ve been working on this essay for over six months now), in between documenting the day’s programming with my camera. Students, alumni, and community members gathered on blankets, mats, and folding chairs under canopy tents with banners and posters and mini Palestinian flags everywhere. Shit is real.] Which is why when this “poem” by Vinay Krishnan “there’s laundry to do and a genocide to stop” (the quotations are not there for a kind of snooty formalism, but to indicate how mixed the reception of this piece was) circulated on Instagram (with largely positive reactions) and X, formerly Twitter, (with decidedly negative reactions) in early March, the need to continually scrutinize art (i.e., prop and its mass circulation) and reading practices (i.e., consumption and critical inquiry) became all the more urgent. Granted, Krishnan may never have explicitly claimed for this piece to be a “revolutionary work,” but he did put in his Twitter bio and website that he’s an organizer for the Center for Popular Democracy.

The driving question for this essay is as follows: how can we make what seems like intimidatingly-complex politics not only intelligible, but also urgent to public audiences who have been systematically de-politicized and distracted? In other words,

“What project, in other words, will most unsettle a community’s fundamental assumptions, lead them into thinking differently about the social and political meaning of cultural contexts in which they are heavily invested?” (Nelson 1011)

In this essay, I am considering under what specific criteria can art be a mode of activist inquiry and insistence. What is the point of feeling moved by art if it is not then to move? If we lose sight of art as a political instrument, a potent ideological weapon, art becomes art for art’s sake, a validated coping (i.e., an aesthetic putting-one’s-head-in-the-sand or gazing-behind-the-safety-of-glass-walls) instead of an earnest reckoning with the rotten system’s foundations. Art at its very best radicalizes, at once directing our sight to sharpening contradictions and readying us as active agents in transforming the world as we know it.

My personal examination of the relationship between politics and formal aesthetics is not meant to be a comprehensive Poetry or [Insert Artistic Mode] 101. I am not posturing myself to be the authority on the poetic craft, nor am I trying to decisively determine whether Krishnan’s piece can be read as poetry. I am a cultural worker taking notes on critiques of Krishnan’s viral piece so that we can apply these lessons to our own prop work and campaigns.

“Let us take a knife

And cut the world in two–

And see what worms are eating

At the rind.”

(Langston Hughes, lines 5-8 of “Tired”)

Let’s start with some definitions (made more digestible, so a background in art history, cultural studies, political science, or anything of the sort isn’t needed to engaging with this essay:

“Form concerns such aspects of the poem as tone, pitch, rhythm, diction, volume, metre, pace, mood, voice, address, texture, structure, quality, syntax, register, point of view, punctuation and the like, whereas content is a matter of meaning, action, character, idea, storyline, moral vision, argument and so on” (Eagleton 66).

Form – “an arrangement of elements— an ordering, patterning, or shaping” (Levine 32), i.e., the style or way in which ~something~ is presented such that this ~something~ lends itself to a certain effect

Content – the immediate subject matter of a work, object, or occurrence

Now, examples using mediums that I engage with most:

Fiction

Formal elements – perspective, structure, characterization, etc.

Content – a girl in high school falls in love with a vampire who has the “skin of a killer” (I watched the entire saga during a recent weekend with my SO, so this is fresh on my mind haha)

Photography

Formal elements – color grading, depth of field, negative space, angle/perspective, etc.

Content – a student graduating from college

Peer-reviewed scientific articles

Formal elements – word count, inclusion of diagrams/graphs/charts, standard structure of abstract-introduction-methods-results-discussion, etc.

Content – empirical findings from a clinical trial

Poetry

Formal elements – rhyme, meter, metaphors/conceits, line breaks, enjambment, spacing, etc.

Content – the life of a queer Filipino in diaspora

Form and content are meant to work in tandem to propagate meaning. The significance:

“It is the work of form to make order. And this means that forms are the stuff of politics… And if the political is a matter of imposing and enforcing boundaries, temporal patterns, and hierarchies on experience, then there is no politics without form” (Levine 3).

This meaning-making process of form and content working together does not sprout organically from our thoughts, but rather, is socially informed and entangled—

“Meaning is not an arbitrary process in our heads, but a rule-governed social practice; and unless the line ‘Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?’ could plausibly, in principle, suggest fried bananas to other readers as well, it cannot be part of its meaning” (Eagleton 1103).

For example, if I were to write, “And I oop,” I’m sure most of you would know the video I’m referring to and that it’s not just a phrase I made up right now.

In his book How to Read a Poem (2007), literary theorist Terry Eagleton discusses poetry as moral statements, rhetorical performances, and material social forces. To borrow from Ismatu Gwendolyn’s writing (although let’s be real, when is my writing ever not inspired by Ismatu):

This understanding of poetry means that poetry has a kind of potential energy (to make a rudimentary physics analogy here, bear with me) to be political, i.e., the poet chooses what is focused on within a piece. What makes that potential energy kinetic? How can this potential energy be set in motion? Well, to continue the physics-themed conceit4, the poet must “position” the poem strategically “in relation to a reference point.” And that reference point, as I state in my boldened thesis statement above (re: in this essay…), is sharpening contradictions, i.e., the conditions of the most oppressed/exploited in relation to the extravagance and excess of society’s “elite.”

This scientific understanding of our varying positionalities is not to be conflated with a kind of oppression Olympics that has us competing to be pitied and selected as a posterchild by the upper elite, but is one that aligns with the principle of conducting concrete analyses of concrete conditions. Our BIPOC, LGBTQ+, immigrant neighbors are unhoused, malnourished, criminalized. I need to acknowledge I have my share of traumatic interactions with medical and higher education institutions at the same time I recognize I have a steady stream of income, health insurance, two working parents with graduate degrees, citizenship, etc. Remember the ground is uneven and unsteady.

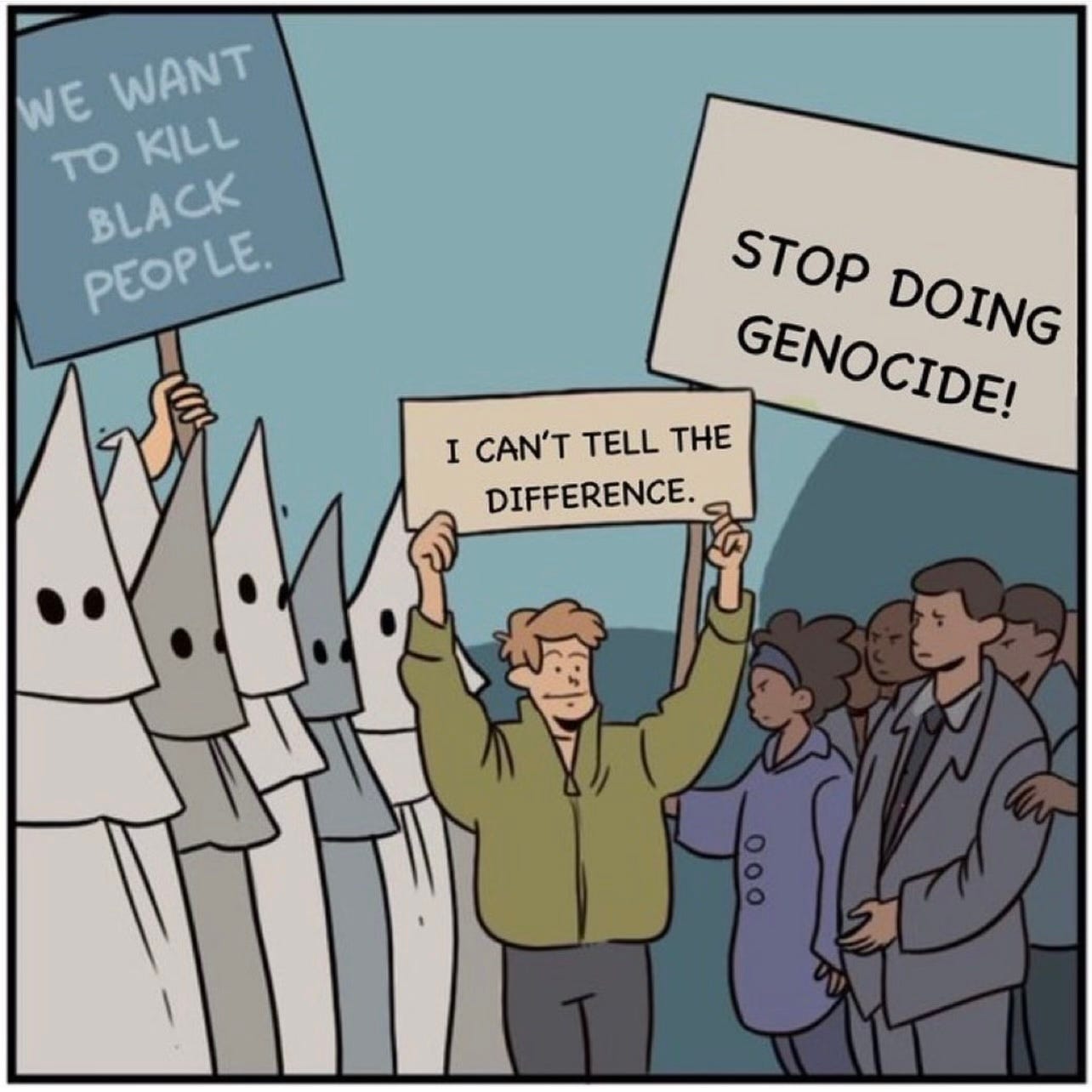

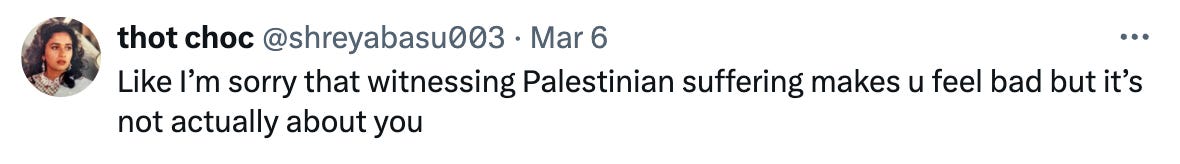

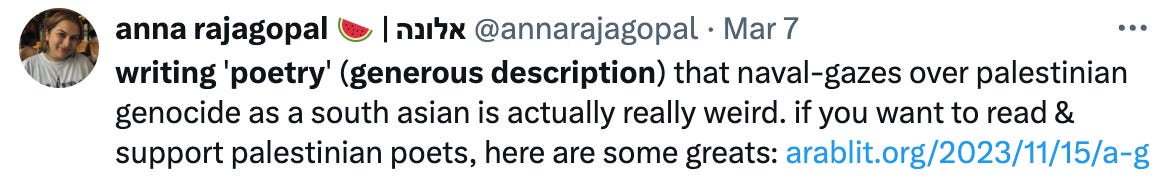

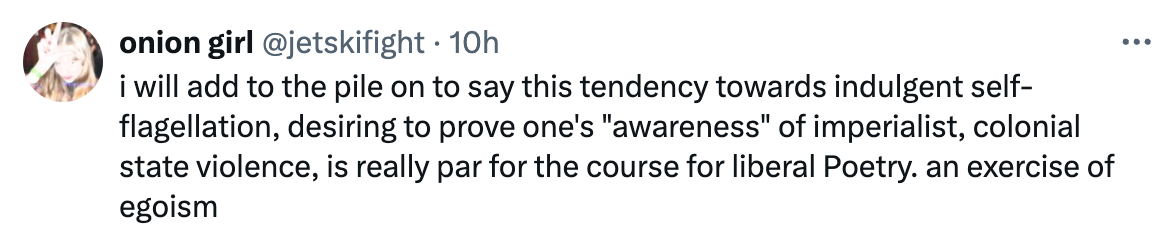

Hence, a major critique of Krishnan’s “there’s laundry to do and a genocide to stop.” It wasn’t so much consciousness-raising as it was introspective (okay, cool and all, but Lenin might view the details in Krishnan’s piece as a manifestation of “fatty degeneration” - see the next block quote below exhibit of Twitter screenshots) and ill-timed and poorly-framed at that:

As “meaning is not an arbitrary process in our heads, but a rule-governed social practice,” many took issue with Krishnan’s first-person perspective and the self-reflective content in his piece ~within the context of~ the broad, urgent movement to free Palestine from Isra*li ap@rth3id and U.S.-backed gen0cid3 (Eagleton 110). Notably, this critique is not one specific to the poetic form, but rather one that asks us to simply read the (politically-charged) room. There are multiple ongoing gen0cid3s from Sudan to the Congo to Indigenous peoples in the Philippines and Turtle Island that aren’t visible in mainstream media (i.e., big news outlets), so why use Palestine, and specifically Rafah, as an avenue to construct the individual dissonance in the imperial core, especially now, when these contradictions have not newly-materialized? Krishnan’s piece seemed rather appropriative of this now-deemed “relevant” crisis.

Yes, while literary critics generally agree that the author of a piece is not the same as the speaker or narrator of a piece (which I write because literary criticism isn’t an attempt to psychoanalyze the author or rehash a biographical account), Krishnan’s positionality as a writer in the imperial core must still be considered. In having the capacity to observe in an environment that’s not immediately threatening (disclaimer, I don’t know the intricacies of Krishnan’s life), Krishnan chose to write ~from~ the “I” perspective, the content of the piece focused on a narrow subset of society that’s not on the front lines of U.S.-manufactured missiles. This could have been a productive rhetorical decision, if it had interpellated us middle-class to upper-middle-class folk as being capable of breaking through the ideological state apparatus tied to Western hegemony, but arguably, that’s not what the piece accomplished (or perhaps even intended to accomplish).

Moreover, Krishnan supposedly publicized his portfolio instead of following up the widespread attention his piece received with resources to materially help Palestinians in the G@z@ strip. Regardless of whether Krishnan thought it would be easy enough for people to find the links to fundraisers for Gazans (and I’ve seen this uncritical willingness to give internet users the benefit of the doubt among my own friends as well, where an educational graphic is reposted on a story but the audience is not directly guided to the said resource/s, an activity that has been termed slactivism) or that raising awareness was enough, this was a self-promoting choice. Is this self-centering what’s needed for the underlying root causes of deathmaking to be challenged? Who needs to be granted visibility, and who gets to be granted visibility? How is this determination made?

Along that same vein, there’s something to be said about why this piece by Krishnan in particular (as opposed to the works of martyred Palestinian professors and journalists) went as viral as it did…

That would require a broader investigation of the priorities of mass culture under capitalism imperialism (i.e., cultural critique). Who were the consenting consumers in this case? In what digital geographies did this piece circulate and resonate with users? More important, what does this say about their level of agitation? I may not have the data analytics to readily look into those questions, but it makes me think about the line drawn between “high literary” culture and popular culture and, as an example, the criticism Rupi Kaur faces for writing popular poetry considered “not good” (you might recognize Kaur’s name from her popular poetic collections milk and honey and the sun and her flowers). Can working class Americans, Americans working paycheck to paycheck, Americans who are one medical emergency away from insurmountable debt, name people in their circles that read literary magazines or point out where Palestine is on a world map (this is not to dog on working class Americans, but to ground our educational and artistic productions in practical considerations)? Does our art need to be a certain level of palatable and #relatable to the Instagram crowds consisting of largely depoliticized residents of the Global North?

The ideal artist under capitalism is one that is unique in their genius, always novel, untiringly and passionately productive in facilitating a strangeness that’s not objecting (i.e., not critical of the current order). The ideal artist under capitalism does not have to concern themself with public or popular education, but instead with careerist aspirations. This egocentric, self-absorbed kind of art-making is fundamentally incompatible with grassroots organizing, as the task at hand is no longer integration with the masses and the abolition of class-based society as we know it (omg, take a breath here). [Mind you, this holier-than-thou stance is another individualist, liberal pit that any artist or cultural worker can regress into. I don’t care how principled you were yesterday; re-molding (unlearning colonial and liberal mindsets and practices) is an everyday, lifelong process.]

In 1905, Lenin envisioned the standards of proletarian literature:

When the answer to the question, “Art for whom?” is clearly those most directly in harm’s way, we can be assured our prop and cultural work is suitable, at least on the level of content, for the working classes’ needs.

Premise I (On Subject Matter or Content): Art within radical movement-building must have an intimate understanding of whose perspective is centered and should aim to uncover the conditions of the most oppressed rather than merely function as an outlet for self-expression (i.e., time and place, babes!).

Radical writings might also be referred to as “literature of social protest, resistance literature, leftist literature, radical literature, partisan literature, literature of commitment, revolutionary literature, literature of alternative hegemony, proletarian literature” and what-have-you, but the principle of focusing content on mass struggles remains.

So, if Krishnan’s piece was focused on incarcerated populations, political prisoners, or unhoused folks that have no access to nutrition or healthcare instead of his relatively-privileged livelihood, would that make for a more effectively-agitating piece? Put otherwise, arming people with knowledge, is that enough? Not quite. [My educational background happens to be in the social/behavioral sciences, and studies have shown the educational interventions on their own are not enough to bring about behavioral change that’s sustained over time.] For example, just because I know eating a lot of carbs won’t give me the energy I need throughout the day, does that mean I won’t eat two packs of pancit canton for lunch and dinner? No, not at all. Or if I pass out flyers with definitions of fascism and imperialism and labor export to fast food workers, does that mean they will cast off their uniforms and overturn the tables and chairs of the establishment? Ha, wouldn’t that be great, but no from secondhand experience.

We need an activator, something that switches that potential revolutionary energy present in the art into kinetic, embodied, realized, radical action— this is where I view the relationship between content (what we discussed for this essay’s first premise) and form comes into play— something that was apparently disjointed in Krishnan’s piece (i.e., how does its form shore up its meaning? well, the iPhone notes-esque form may give the piece the appearance of the formal considerations of art not being given much thought, although one could argue it’s precisely because the Krishnan speaker writes, “I don’t have time to think through the / implications because there’s laundry to do and a / gen0cide to stop”).

Below, I’ll use two current examples of artistic productions (musical theatre and folk music) that conveyed political messages with poignancy and have a better-positioned potential to raise political consciousness.

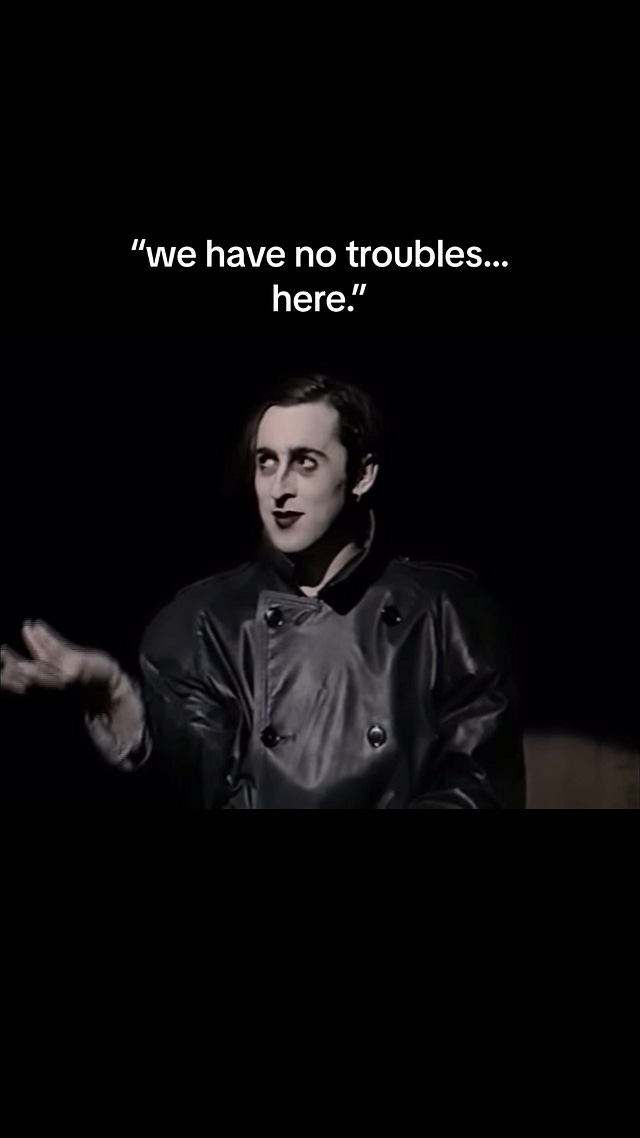

Lately (at least when I was writing this essay section earlier in the summer), I’ve been on Cabaret TikTok, so I’ll discuss Eddie Redmayne’s “Wilkommen” performance at the 2024 Tony Awards. Whether or not you think Eddie Redmayne version of the emcee was well-portrayed, many folks on TikTok who had never seen the musical before (same) noted the uneasiness they felt watching the performance. Something felt off, they said. Many theatre fans were quick to explain the premise of this musical which is set against the political backdrop of the rise of a certain fascist German political party.

“Set in 1929–1930 Berlin during the twilight of the Jazz Age as the N*zis rise to power, the musical focuses on the hedonistic nightlife at the seedy Kit Kat Klub and revolves around American writer Clifford Bradshaw's relations with English cabaret performer Sally Bowles. A subplot involves the doomed romance between German boarding house owner Fräulein Schneider and her elderly suitor Herr Schultz, a Jewish fruit vendor. Overseeing the action is the Master of Ceremonies at the Kit Kat Klub, and the club itself serves as a metaphor for ominous political developments in late Weimar Germany.” (Wikipedia)

There are visible cracks in the flashy, carefree spirit of the performances, of which one example is the purposeful choreography of Redmayne’s emcee in the opening number. Look carefully at the photo below; his arm and hat placement should look disturbingly familiar…

From what I understand about Cabaret, the show follows characters at a boarding house who become more overtly embroiled in political tensions, in spite of the characters’ efforts to believe, “We have no troubles here.”

The hope is for the storyline and music (e.g., contrast between the first and final “Wilkommen” numbers) to get theatregoers to reflect at what cost (really, at whose expense) can we delude ourselves into remaining in an apolitical bubble? Does that matter to us (and who is included in the “us”)? If not, why? What will it take for something to matter? Proximity? Convenience? When all other distractions and numbing devices cease to be an option?

If these themes still don’t “click” for the audience, the final scene takes a more direct approach to getting the audience to confront their own politicization. It comes as a major shock to the audience when the Kit Kat Club’s emcee reveals something key about his character’s identity, and it elicits nothing short of the dramatic effect of ornate curtains dropping to reveal a dirty, dilapidated backstage. [The scene somewhat reminds me of when Dorothy meets the true Wizard of Oz, a mere man instead of a grand magician.] You can watch the 1993 (I think?) Cabaret production with Allen Cummings’s version ~4:30 into the YouTube video embedded below. [Just know there are spoilers if you choose to watch the video and/or keep reading beyond this point!]

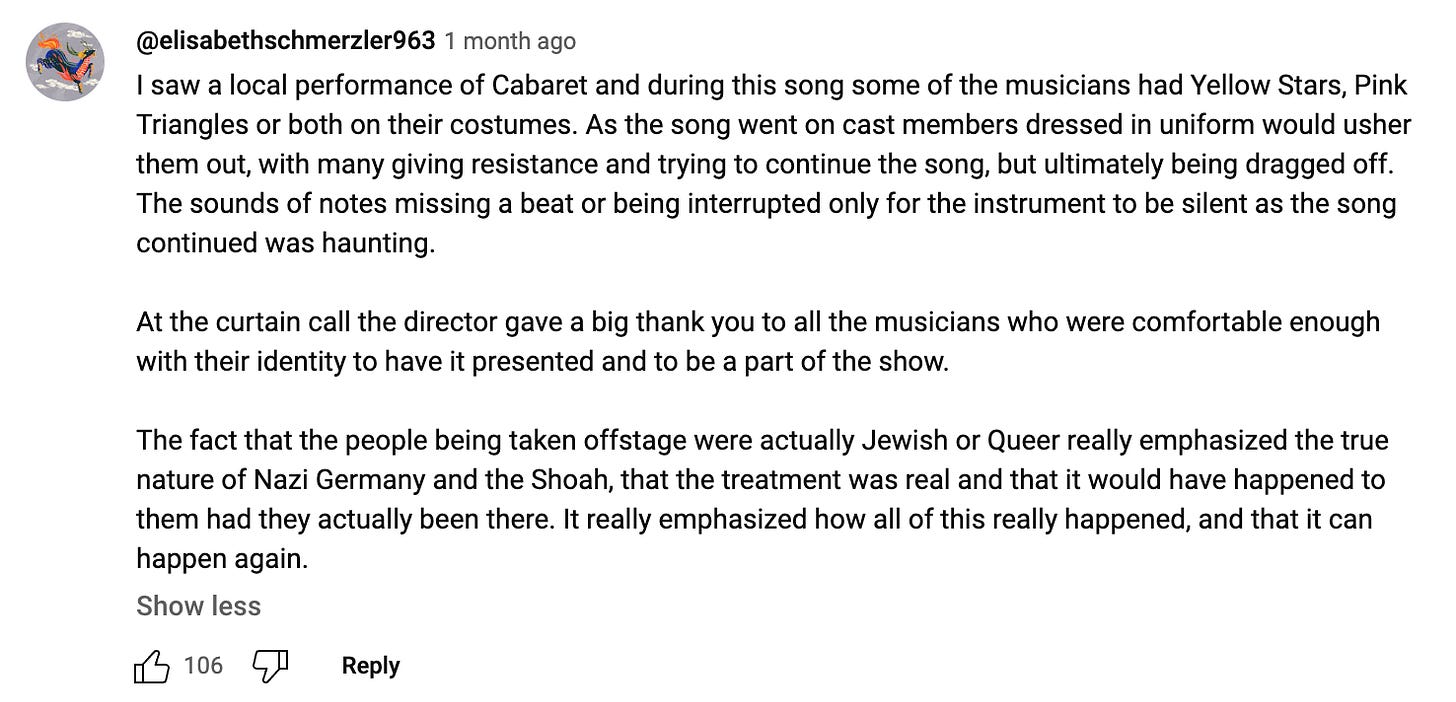

After reading TikTok and YouTube comments (which are sometimes more informative for me than the actual content of a video), I learned that Cabaret has different versions of the ending scene. In a comment I no longer remember where to find (because I took a while committing these thoughts to the page), someone wrote about a Cabaret production that had suspended mirrors as part of the stage setting so that the audience is forced to look at themselves as they witness societal deterioration portrayed through interactions between everyday characters. Now that is prime (lol) interpellation (an Althusserian term that describes the process of individuals becoming constructed through and included in pre-existing social structures), in the sense that the audience sees themselves as implicated in the story’s politics. It could be them (and us!) on stage being a historical lesson.

The second example requires less contextualizing. Several indie and folk music artists have popped up on my TikTok whose songs reflect on current domestic and global politics, with the proceeds generated by some of the songs’ streams going to Palestinian fundraisers. Here are a few of the ones I’ve seen and been particularly affected by:

· “Who Would Jesus Bomb?” by Jordan Smart – One of the lyrics in the chorus is, “Would Jesus bomb the atheists, the Muslims, or the Jews? I want you to ask yourself well what would Jesus do?”

· “War Isn’t Murder” by Jesse Welles (the TikTok below isn’t the original singer-songwriter; I just liked this cover) – One line that hit hard for me was, “[War is] a nation-state’s sanctioned righteous hate.”

Tiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser· “What Are You Praying For?” by Marieke Liebe – This song’s imagery is more localized, which made the horrors being described that much more vivid and palpable to me. It just made me think, “Who could really be okay with this?” This song is also gathering donations for Operation Olive Branch through streams.

@ohmariekewhat are you praying for? SONGWRITERS, PLEASE READ: i’ve been resistant to sharing my writings about 🍉🍉🍉 because of various fears. after having a few dialogues with friends about it, ive realized its important to be reflecting the external world as well as expressing the truth of what feelings exists within me. there have been a handful of radical songwriters popping up on my page that have shown me that all of our voices matter, all of our impacts matter, no matter how small. writing helps us to work through and process our own feelings, can help us heal, bring us together. so i ask, if you are a songwriter, challenge yourself to write and share a song for liberation and justice. and if you are interested, we can put it all on a compilation album on Bandcamp and raise some funds. also, if you stream or purchase my music, 100% will be donated to help g*z*. #protestmusic #protestsong #operationolivebranch #fypツ

@ohmariekewhat are you praying for? SONGWRITERS, PLEASE READ: i’ve been resistant to sharing my writings about 🍉🍉🍉 because of various fears. after having a few dialogues with friends about it, ive realized its important to be reflecting the external world as well as expressing the truth of what feelings exists within me. there have been a handful of radical songwriters popping up on my page that have shown me that all of our voices matter, all of our impacts matter, no matter how small. writing helps us to work through and process our own feelings, can help us heal, bring us together. so i ask, if you are a songwriter, challenge yourself to write and share a song for liberation and justice. and if you are interested, we can put it all on a compilation album on Bandcamp and raise some funds. also, if you stream or purchase my music, 100% will be donated to help g*z*. #protestmusic #protestsong #operationolivebranch #fypツTiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser· “Untitled” by Oliver Richman – This song was written in reference to a photo of Republican politician Nikki Haley signing “America ❤️ Isr*el” on a projectile. Imagine having hatred so deeply ingrained in you that you proudly write your name on weapons of mass murder.

Tiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser· “Don’t Politicize” by Philip Labes – I think this song (and the caption) offer an accessible introduction to political violence for those who never really considered the extent of it.

@philiplabesPolitical violence IS wrong, and there are many kind of political violence — the systematic destruction of the middle class and the social safety net, gun deregulation and school shootings, destroying our climate, removing reproductive rights, legal attacks on queer existence, funding a genocide... these are all violence too. If we’re against violence, let’s be against violence.

@philiplabesPolitical violence IS wrong, and there are many kind of political violence — the systematic destruction of the middle class and the social safety net, gun deregulation and school shootings, destroying our climate, removing reproductive rights, legal attacks on queer existence, funding a genocide... these are all violence too. If we’re against violence, let’s be against violence.Tiktok failed to load.

Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

To be clear, the objective of revolutionary art is to unite the broad masses and incite direct action that topples the existing, oppressive order. I'm not sure I would call the Cabaret musical necessarily “revolutionary” or “proletarian-spirited,” but I will grant that it, along with the folk songs, can be viewed in terms of the affective attachments produced. I specifically chose the above examples as case studies in what literary scholar Jonathan Flatley explores as “affect” and what I think of as the “aha” moment (that sinking-in feeling indicative of a renewed, actionable paradigm):

“Where emotion suggests something that happens inside and tend towards outward expression, affect indicates something relational and transformative.” (Flatley 125)

Although each person’s radicalizing is ultimately their own— each person has to make their own decision on what matters to them and how they respond to it— artists can provide inroads into a collective revolutionary consciousness. The cultural objects we produce warrant much care because the stakes are so high (and I can’t overstate that).

“Affects… involve a transformation of one’s way of being in the world, in a way that determines what matters to one; affect requires objects, and, in the moment of attaching to an object or happening in the object, also take one’s being outside of one’s subjectivity.” (Flatley 19)

Premise II (On Aesthetic Value and Affect): Cultural workers must carefully consider how the form and content may jointly bear an urgent message rousing the spirits of those who have remained in the darkness of Plato’s cave for too long, i.e., let people gradually adjust their eyes to the sunlight.

Some concise final thoughts (because if I don’t wrap this up now, I’ll talk myself out of posting it, and then it may be another six months before I open this draft up again— when I talk about “good poetry,” I’m not referring to adhering to elitist institutional literary standards. Effective poetry (and any cultural work) for the new world, though, requires careful labor to be both truthful and decisive. As Mao said, the revolutionary artist strives for “the unity of politics and art, the unity of content and form, the unity of revolutionary political content and the highest possible perfection of artistic form.” For those of us whose revolutionary role is cultural work— and this goes for any role in the movement— we must continue to hone our craft. Our movement needs, it requires, our art and imagination. How else can we hope to transform our current world?

This past June, I was facilitating a virtual teach-in with land defenders and cultural workers based in the Philippines in June, and one of them said this: “there is no higher creative practice than creating the world.”

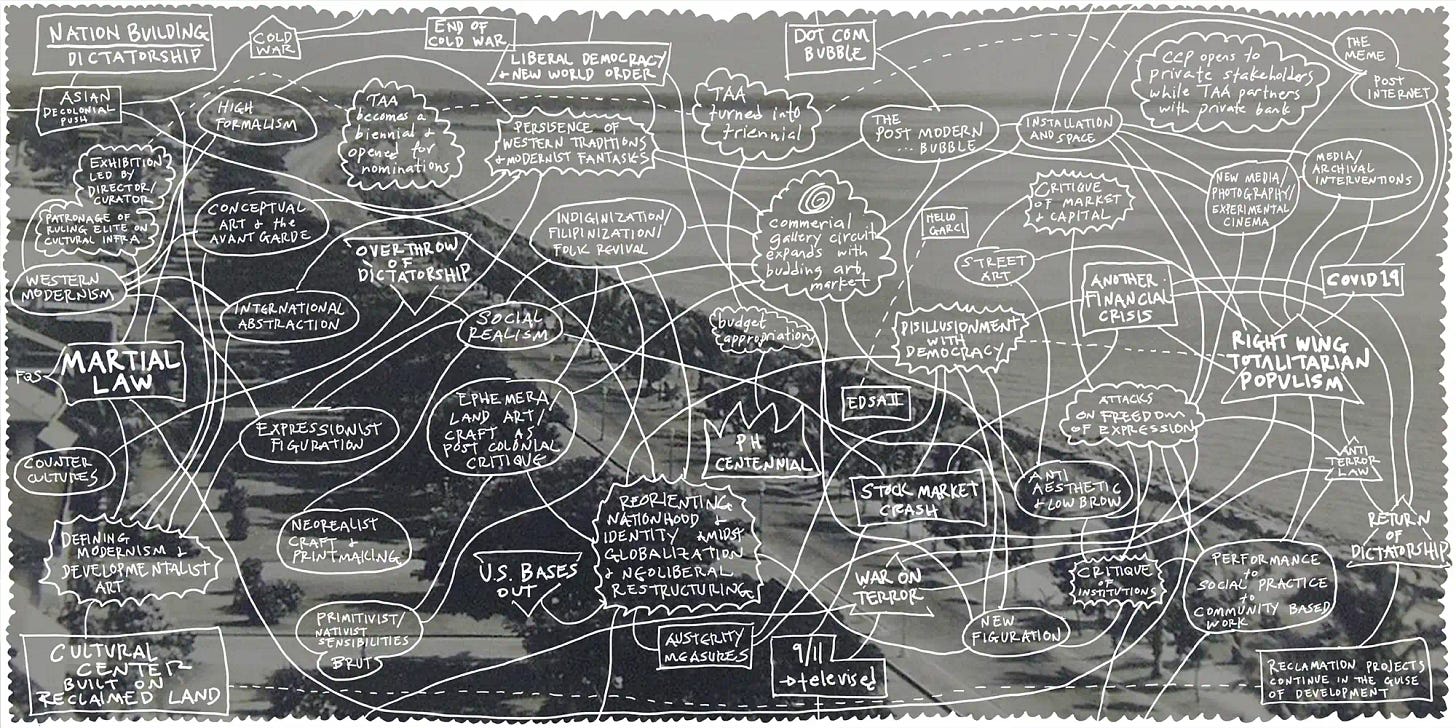

I’m ending this post with Manila-based artist Cian Dayrit’s summer exhibition “Liberties Were Taken” in Houston, which would be a great case study of revolutionary art. I had never seen art so familiar to me in a museum, not because I was taught its formal elements in a classroom but because each piece was literally and intertwined with mass issues in the Philippines. Cian's treatment of maps as palimpsests, threaded with textual commentary, not only traces state violence against indigenous and peasant communities, but also maps the people’s resistance. His work is beautiful as much as it is an act of defiance.

Further reading: “Revolutionary Consciousness” by Cary Nelson in The Critical Pulse: Thirty-Six Credos by Contemporary Critics (2012) edited by Jeffrey J. Williams & Heather Steffen

Further reading: “Introduction: The Affordances of Form” in Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (2015) by Caroline Levine

Further reading: How to Read a Poem (2007) by Terry Eagleton

Conceit - “From the Latin term for ‘concept,’ a poetic conceit is an often unconventional, logically complex, or surprising metaphor whose delights are more intellectual than sensual” (Poetry Foundation).

Further reading: “Glossary: Affect, Emotion, Mood (Stimmung), Structure of Feeling” and “Affective Mapping” in Affective Mapping: Melancholia and the Politics of Modernism (2008) by Jonathan Flatley