The Rungs of the Social Ladder are the Necks of Your Neighbors

Excellence and Assimilation are Flimsy Shields

I write this, incensed from middle managers in sheep’s clothing, BCCs and plausible deniability, wage theft rebranded as exciting new job architecture.

If you were underpaid before, no you weren’t, here’s a $5,000 pay increase. Congratulations, you’re now at the minimum of your new pay grade (get back to work, said with a smile that doesn’t reach the eyes)! And if you weren’t being underpaid, you are now, but don’t be mad because the corpora— I mean, university is generously investing a few million dollars for pay equity (never mind that their endowment is billions of dollars). You should be thankful for the possibility of a merit increase… years down the road… all the while inflation keeps doing its thing… and your tax dollars fund millions of deaths abroad… and rent hikes drain your paycheck… and you have to choose between a meal and healthcare… and…

HR is charged with implementation and apologetics.

Misdirected ire is quickly snuffed out.

The day’s timed labors, the plush insulation of someone else’s devalued productivity, can either be something that sedates you into turning a blind eye or compels you to deconstruct, from brick to building, the conditions of your very existence.

Premise I.I: There exists a political slippage (social contradictions) that everyone at some point experiences themselves, bears witness to, and/or facilitates.

After writing two posts on the empty promises of liberal feminism (see “The Lady’s Shoe Closet: Liberal Feminism Supports Women’s Wrongs, Not Women’s Rights” and “Being a Girls' Girl Doesn't Mean Breaking the Glass Ceiling: The Empty Cheers of Liberal Feminism”), I finally decided on a title for this this node of kanto: “Disturbing the Sediment.” This word “sediment” connects my schooled writing practice of heavy outlining to my guerrilla writing practice of jotting down pre-formed thoughts and pithy phrases, and bookmarking sources in different places. Whether I remind myself of my ideas through a Google document or in an iMessage text to myself, I came to refer to the various idea storage place(s) as “sediment.” I was inspired by my Victorian Fiction professor who called her own repository of writing fragments “sediment,” as she advocated for “k*lling your b@bie$.” [My sediment document(s) have amassed quite a few b@bie$, that’s for sure, since I don’t want to just delete the thoughts I went through the effort of configuring on the page. They all get recycled in the sediment document.]

Sediment, as may be the first thing that comes to mind, also refers to “particulate matter that… over time become[s] consolidated into rock” (thanks, Google dictionary). The hardened ground has become reliable to us because it carries our bodies and our creations every day. It has matured, outlasting civilizations and holding our ancestors’ returns. Widening this perspective’s frame is a surreal process— that hardened ground lies on the shallowest layer of Earth, a suspended, rotating, orbiting mass of water and hot rocks. Suddenly, nothing seems so natural anymore. Everything bears a trace of the history that hurts1.

why isn’t there screaming in the streetsthe children are diabetic the pregnant women are diabeticso many people of color so many poor and working classand the food is making us sickand every day there are more and more of usand la azucar is claiming lives and limbs and whole families

(Ire'ne Lara Silva, lines 72-77 of “diabetic epidemic” in Blood Sugar Canto)

I don’t say this to take away any sense whatsoever of your grounding and cause you panic. I hope to arm you with clarity.

how do i tell you this gently how do i tell you this so that you hear itlike a lullaby it is a warning but i do not want to frighten you i do notwant to plant a seed of fear

(Ire'ne Lara Silva, lines 1-3 of “lullaby” in Blood Sugar Canto)

“Disturbing the sediment” calls for deeper inquiry, a critical orienting of the ground which we stand on. When you dust off and excavate these hardened rocky deposits, it gives way to the historical layers lying just below the surface, layers that were always present, but buried, mystified to us.

This kind of study’s aspirations is not something to be likened to AP U.S. History (APUSH) learning objectives (throwback, and not a pleasant one), in the sense that I am not mandating a certain conclusion. Instead, I am offering a framework that is in itself not absolute; it must be re-assessed and sharpened sharpened against the changing material landscape of each day. Through the critical mode of analysis I am practicing in “Disturbing the sediment,” the APUSH curriculum may very well be a ground to excavate, if you choose. [I just did a quick Google search. In the APUSH Course Framework effective as of Fall 2017, Key Concept 5.12 for Period 5, 1844-1877, states, “The United States became more connected with the world, pursued an expansionist foreign policy in the Western Hemisphere, and emerged as the destination for many migrants from other countries.” Like gorl… don’t you mean imperialism? -_-]

For me, the grounds I’m most interested in destabilizing are in the realms of literature and pop culture trends. For you, it will look different. I have friends who are passionate about sustainable farming practices (they make a living by tending to the land3), organizing beyond the non-profit industrial complex (they work in the non-profit sector4), and spoken word as ideological resistance (they write and perform poetry5). Notably, these areas of focus are not meant to be isolated specializations. They are diverse knowledge bases forming the machinery of a collective liberatory project. [One of the aforementioned friends told me that they didn’t want to be part of a movement that doesn’t allow people to show up in different ways, and they were specifically saying this with regard to people with disabilities, such as myself, who engage in community organizing and mass mobilizations in a different capacity. That provided great comfort to me, as it was a helpful dialectical framing of the guilt I sometimes feel about not being able to show up in the ways that other folks can.]

By following along with my version of disturbing the sediment, I hope you feel encouraged to (i) practice your own ways of disturbing the sediment and (ii) contribute your skills to your communities. [Love to all the local organizers tending to their communities.]

Premise I.II: We all decide whether or not we want to investigate that political slippage, if we’re okay with letting it fester or if we want to be a part of the upending of oppression’s root causes.

This week’s sedimentary disturbance was spurred by the January 2 news of Claudine Gay’s resignation as Harvard University president. [I started writing this essay the first week of January, but I have since been occupied with ~growing pains~ and have been returning to this periodically.] Reactions to Gay stepping down spurred this disturbed affect (“near-imperceptible, too-intense, interstitial, or in-the-making visceral forces and feelings that accompany and broker the entangled material—especially bodily—and conceptual potentials of an emergent or historical phenomenon”) within me that I have been trying to hone in on. I get the sense that many of us are on the cultural precipice of leftist subjectivization (for example, Swifties calling out Taylor Swift using her private jet to fly just 28 miles and in general, being responsible for a wild amount of carbon emissions, after her legal team sent a cease-and-desist letter to college student Jack Sweeney who uses publicly available data to post jetsetters’ movement on social media), getting warmer, but the warmth can only stay so long before it cools down or is put out. I hope this essay is your insulation, so eventually (sooner rather than later) you can find and sustain your own conductor of heat, the revolutionary flame alight within you.

In this essay, I am reflecting on how race is too often considered independent of class, the deep embeddedness between the two being obfuscated by the liberal identity-politic version of decolonizing your mind and at last “seeing color.” It is imperative to recognize how cultural forms of assimilation reify meritocracy, a tenet of the neoliberal moral political economy. My hope is that we emerge from these readings having started to unravel our notions of excellence, i.e., how it is accomplished, for whom, to uphold what, and thus have a better understanding of pervasive neoliberal ideology.

[I find myself almost wanting to bite my tongue, wring my hands. This topic is rife with contradiction in my own personal life (having graduated from a private R1 university and soon to be attending graduate school at an Ivy League), but struggling through these moves and countermoves is what helps us build a durable analytical foundation that informs principled, strategic action. (I made a Catching Fire reference, and I’m really hoping some of you caught it.)]

In beginning to dissect that disturbed affect, I’m recounting all the articles and social media commentary I’ve seen that point out the racial animus behind Gay’s resignation and conservatives’ celebrations of Gay’s resignation. They tend to agree that the attacks on Gay’s professional and scholarly character (whether it is actually her scholarly rigor that fault was found with, her Black womanhood disguised as criticism of her scholarly rigor, or her stance on anti-semitism amidst genocide in Palestine) are symptomatic of anti-intellectualism and a right wing-led crusade against “divisive” educational curricula like critical race, postcolonial, and queer theory.

Something fundamental is missing from these analyses that then renders its conclusion insufficient. Analytical confusion, even stemming from a good-faith attempt to speak truth to power, can have political consequences (and it’s why theory is necessary and ideological struggle is a pillar of revolutionary action). In pinpointing the grounds for Gay’s resignation as any of the following answers I’ve seen— Because she’s a Black woman. Because she’s accused of plagiarism. Because higher education is too radical now, with critical race theory and postcolonialism fueling hatred against white people— race is flattened into an abstract, disembodied idea (the idea that people are treated differently on the basis of skin color) rather than an ideology that, historically, has been made material, i.e., systematized, institutionalized, by people who achieved hegemony and still enforce it through evolving cultural tactics.6

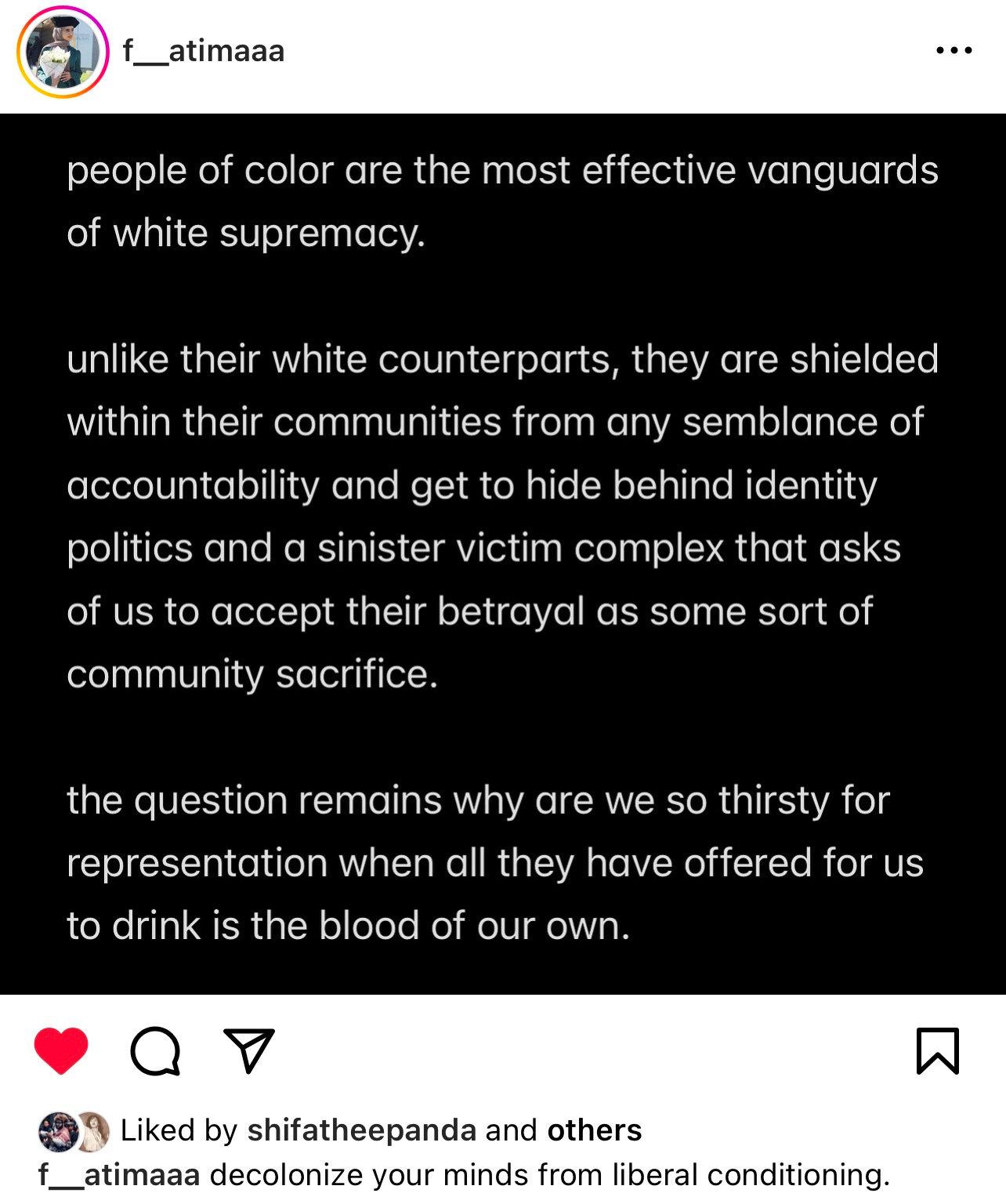

Let’s think about it this way (reverse engineering how this type of analysis is reductionist). What is the conclusion drawn from condemning the racial animus behind Gay’s resignation? Perhaps it’s that Gay should continue to serve the rest of her tenure as Harvard president, and more broadly, Black women, and any person of color really, should have their hard work recognized by being allowed to lead prestigious institutions. The issue I take with this conclusion, and the analytical confusion giving way to it, is its “business as usual” framing that enables Black women and other people of color to hold seats of visibility (maybe even authority) within exploitative institutions; it obliges us into mistaking a Black woman president as something intrinsically “good” and any shifts in cultural formations as automatically translating to material reckonings with structures of power. Is the long-term goal not to unsettle racism, rather than fall into step with it?

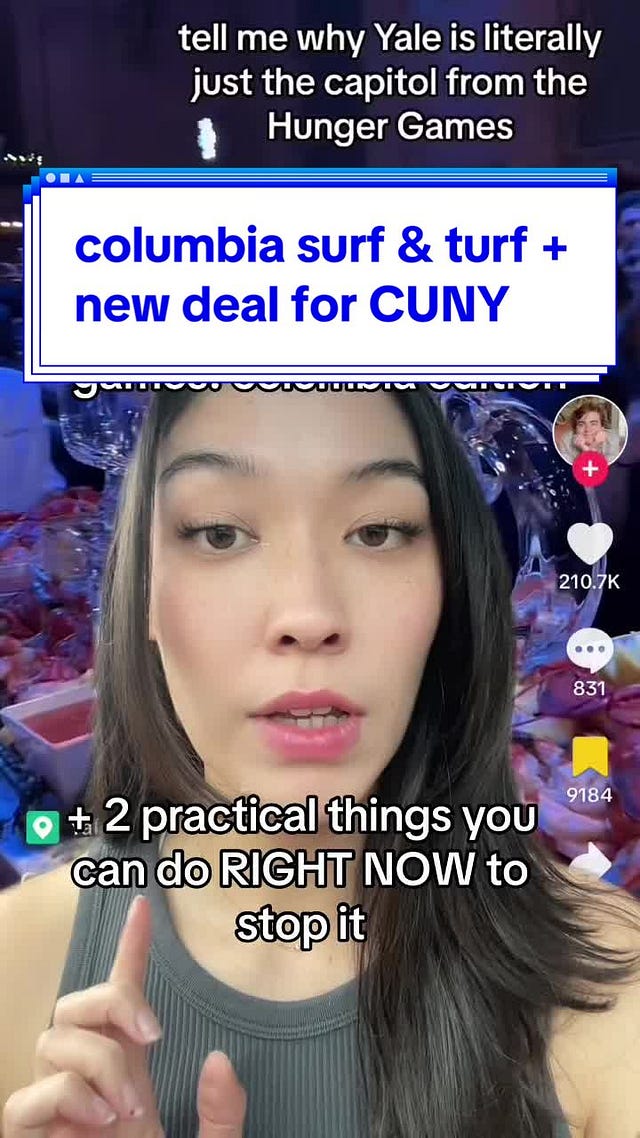

Gay’s presidency was beneficial to the Corporation (this is literally what the smaller and “more powerful” entity within Harvard’s board of trustees is called, and it’s just kind of astonishing, not in the good way, how their capitalist bureaucracy is in our faces), until it wasn’t. If you hazard a guess that Harvard’s funding was threatened because of Gay’s testimony before Congress on anti-semitism on college campuses and plagiarism allegations, I’d wager you are exactly right. Keep in mind the Corporation advertises their status as “the oldest corporation in the Western Hemisphere,” so it’s certainly not just their esteemed reputation they’re concerned about, but generations of wealth and capital they have amassed through “investing” in higher education and research. To that point, I would recommend going to 00:36ish seconds in the TikTok below, where Yale alum and now labor organizer Caitlyn Clark explains Ivy League universities as hedge funds, a big part of their investment portfolio being real estate.

Claudine Gay’s academic credentials don’t have to be sneered at in order to reach the understanding that universities, just like corporations, will protect their bottom line at the expense of people of color. Racialization (the making of race into a social category of difference) must not be taken as an end in itself, lest we ignore its situatedness in historical class formations. An analysis that condemns anti-Blackness as a singularity, as a form of bigotry that stands on its own, is ineffective precisely because it is only skin-deep, failing to consider its form in the long durée of capitalist modernity. Moreover, to stop after recognizing the racial undertones behind Claudine Gay being made to resign by the Harvard Corporation is to settle at pointing the finger at conservatives for racist and anti-intellectual demagoguing, and miss how liberal centrists are implicated, incriminated, too in all their touted “progressiveness.”

Premise II.I: Identity politics allow institutions like Ivy League universities to fly under a more “culturally-acceptable, politically-correct” liberal banner, even though they continue to operate as hedge funds that disenfranchise working class communities.

Because this essay is concerned with how economic structure (free-market capitalism, deregulation) informs the dominant ideology of race, I want to retrace how there comes to be a recursive relationship between the two that falsifies it into a chicken-or-the-egg question. From a historical-materialist perspective, social organization is what begets and underlies the hegemonic ideology. Societal ways of thinking, then, are exposed to productive social formations, and this chronology in the Marxist spirit helps us follow the reconfigurations of schools of thought (see the dehistoricization bulletpoint example of original sin being supplanted by more modern notions of human nature as inherently evil in a recent kanto post I made).

I was a student in my first year at university when I first thought to historicize racialization. There is a certain phase my professor at the time taught me that has remained with me as I started to take courses in health disparities— “the tyranny of the empirical.” If my memory is accurate, this phrase was taught in relation to an assigned reading of a well-known essay by Barbara J. Fields entitled “Slavery, Race and Ideology in the United States of America” (1990).

Why did chattel slavery emerge? Why Black people specifically? Did European people suddenly wake up one day and decide they don’t like Black people? Was there an intrinsic hatred for people with darker skin? (The operative word there is “intrinsic.” This question’s analytical thrust is not materialist and therefore can’t be Marxist.) Landowners in early British North America began to systematically enslave people from Africa and the Caribbean toward the late 17th century (Fields 101). Fields reasons that the switch from economic reliance on indentured servitude to enslaved African and Afro-Caribbean people could have occurred with a few political logics informing it: enslaving lower-class, white indentured servants would discourage future voluntary immigration from Europe; more importantly (according to Fields), African and Afro-Caribbean people did not participate in UK-specific class struggles, and therefore the historical lessons that emerged from specifically-English social reckonings were not applicable to African and Afro-Caribbean people; and African and Afro-Caribbean people began to live longer as tobacco prices dropped in the 1660s, and it became cheaper (more “practical”) to enslave them for life (101-5).

I include Fields’ brief chronology here because, interestingly, she pinpoints Black racialization and thus, racism, as emerging after slavery. Just sit on that thought for a moment. This was, pardon my French, a mindf*ck to me when I was a first-year. Wouldn’t you think that white colonialists enslaved African and Afro-Caribbean people because they were Black? On the contrary. Fields states:

“Race as a coherent ideology did not spring into being simultaneously with slavery, but took even more time than slavery did to become systematic. A commonplace that few stop to examine holds that people are more readily oppressed when they are already perceived as inferior by nature. The reverse is more to the point. People are more readily perceived as inferior by nature when they are already seen as oppressed. Africans and their descendants might be, to the eye of the English, heathen in religion, outlandish in nationality, and weird in appearance. But that did not add up to an ideology of racial inferiority until a further historical ingredient got stirred into the mixture: the incorporation of Africans and their descendants into a polity and society in which they lacked rights that others not only took for granted, but claimed as a matter of self-evident natural law.” (106)

and,

“Racial ideology supplied the means of explaining slavery to people whose terrain was a republic founded on radical doctrines of liberty and natural rights; and, more important, a republic in which those doctrines seemed to represent accurately the world in which all but a minority lived. Only when the denial of liberty became an anomaly apparent even to the least observant and reflective members of Euro- American society did ideology systematically explain the anomaly… It was not Afro-Americans, furthermore, who needed a racial explanation; it was not they who invented themselves as a race. Euro-Americans resolved the contradiction between slavery and liberty by defining Afro-Americans as a race.” (114)

To reconstruct Fields’ timeline from my understanding: indentured servitude and some enslavement on the side (i.e., not systematic slavery) → enslavement of African and Afro-Caribbean people as the more “economical” option for white landowners (slavery was systematized, and slave codes were established) → class contradiction of “liberty for all” not actually applying to everyone → construction of racial ideology in which Black people become an “inherently” inferior race to justify their exploitation (the inferiority of this new race as being ordained by God) → scientific racism.

The tyranny of the empirical factors in towards that last part of Fields’ timeline (“construction of racial ideology…”), in that skin color is something observable (empirical) and natural, thereby being ordained by God (see the naturalization bulletpoint in one of my recent kanto posts) [Fields explains this naturalizing of racial difference in her essay, but what I say next is my own supposition]. With medical and technological innovations, scientific racism was further “evidence,” i.e., justification, for the systematic oppression of Black Americans.

Premise II.II: The tyranny of the empirical describes the dehistoricizing of capitalist racialization, the severing of the material tie between its emergence and its liberal ubiquity.

If you look up neoliberalism, you will first be directed to free-market economic theory (“neoliberalism as a politico-economic doctrine that embraces robust liberal capitalism, constitutional democracy, and a modest welfare state”). You can refer to Section 7: “Criticisms of Neoliberalism” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (so handy dandy) to get additional background on what I discuss in this last section of the essay.

When I think of neoliberalism, I think of profit over people and meritocracy (to what degree they are symptoms or core facets of neoliberalism, I am unsure, at least according to the Stanford Encyclopedia’s research synthesis). “Profit over people” is easier to condemn writ large, but meritocracy is more seductive; it undergirds the promise of social mobility and recognition.

I think back to the Black Lives Matter resurgence in 2020, when I was texting two of my white friends from rural Louisiana (where I was part of the 0.2% Asian population for a significant portion of my upbringing). One of them (let’s call her Lucy) was horrified at the murder of Elijah McClain (God rest his soul) by Colorado police and paramedics. Elijah was largely being described in the media as someone who wouldn’t hurt a fly and on the autism spectrum (although his family has since disputed the latter), and Lucy was particularly disturbed that officers could harm such a gentle soul. Elijah’s last words, as caught on police body camera footage were:

“I'm an introvert. I'm just different. That's all. I'm so sorry. I have no gun. I don't do that stuff. I don't do any fighting. Why are you attacking me? I don't even kill flies! I don't eat meat! But I don't judge people, I don't judge people who do eat meat. Forgive me. All I was trying to do was become better. I will do it. I will do anything. Sacrifice my identity, I'll do it. You all are phenomenal. You are beautiful and I love you.”

I told Lucy it really shouldn’t matter how much of an upstanding citizen a person of color is because everyone should be afforded the right to being treated with integrity and respect. When I texted this to her, what I appreciated (and still appreciate, as Lucy is someone I adore greatly to this day) was that she recognized that what I said wasn’t invalidating her reaction, but dialoguing with her awareness of this social contradiction (e.g., racially profiling and enacting brutality against a Black man who did nothing to provoke an attack of such force versus judges letting white r@pists go with a slap on the wrist). Perhaps it was in that moment that Elijah McClain’s murder exemplified to Lucy how people of color are not shielded from violence and oppression by peaceful dispositions. As American civil rights activist Kwame Ture said, “Peace is the white man’s word. Liberation is ours.”

It is along this same vein of logic that I write about how individual or even cultural excellence is also not a viable strategy for avoiding being the targets of state and interpersonal violence, much less abolishing deeply-rooted structures of violence. Gay’s resignation from the Harvard presidency is just the most prominent and recent example of this in the media. Under the same umbrella of respectability politics as Black excellence, model minority is another sly iteration of neoliberal meritocracy. [This is coming from someone who used to buy into model minority, having this self-effacing pride from being stereotyped. Weird behavior.] Liberal and conservative (there is a false binary between the two) capitalists then exploit the supposedly Asian “virtue” of performance to justify continued exploitation of other communities of color and Indigenous communities, while fragmenting Asian/-American communities from the inside (because people contain multitudes and can’t fit into a cookie cutter standard, so guess what happens when you diverge from the stereotype… hm…).

Early last year, I had a brief conversation with a friend (let’s give her the alias Aria) via Instagram DMs. Aria slid up on my close friends story, as I had posted about bombastically side-eyeing (if you’re on TikTok, you know what I mean) liberal feminism. She wrote me back, saying she thought I was liberal but it sounded like I was “mad a liberals…?”. [Ngl, I was offended by this because I had been participating in leftist community spaces for over two years at that point. Granted, Aria was not in those circles, so I understood why “liberal” was as far left as she had directly seen. And still, if I was pushing a liberal political line, I needed to have that pointed out.] After telling her I’m anti-liberal and anti-neoliberal and asking her, “What can I clarify?”, she asked me about Marxist feminism (insert Lola Tung’s viral TikTok sound “ohmygoodnesss I love this questioonnn”). I, being chronically online, sent Aria a TikTok with a concise explanation of liberal feminism’s assimilation into capitalist patriarchy. The second-to-last thing she told me (the last thing being a courteous thank you) was that she still thinks women should be empowered to take leadership roles (i.e., be baddies) but not unethical ones. The last thing I wrote back to her was how my personal politic reverses leadership and the masses (from top-down to bottom-up), whereby the masses are whom revolutionary movements are wrought from. I wish I got to expound on that in the conversation, so I’m doing that here. [Yes, I’m one of those people that continually thinks about conversations and what I could have said after they’re already over.]

I’ve fixated on that word she used, “unethical.” What does that mean to her, and what does it mean to me? Is it the same for us? What does uplifting women mean? This is not to place myself on a woke pedestal (a reactionary liberal tendency), but to earnestly consider the conflation of women’s liberation with women’s (capitalist) empowerment. As I wrote earlier in this essay, analytical confusion has real political consequences. As I reflect on what’s ethical and what’s not, I realize I do not consider actions to be insular (e.g., women taking unethical leadership roles), but rather enmeshed within a sprawling politico-economic latticework.

As a thought experiment, if the current CEO of top consulting firm Accenture, Julie Sweet, is not directly responsible for decision-making processes that result in thousands of her employees being overworked, is her leadership still ethical? My point in that question is Julie Sweet still profits from her workers, regardless if she was the one to spearhead the corporate culture at Accenture, a mere figurehead, or a middle manager that liaises with employees on the behalf of top stakeholders’ interests. [A quick Google search shows Sweet’s yearly salary to be anywhere between $20 to $30 million, whereas an Accenture consultant on average earns at or above $100k. And yes, while $100k is a lot more than most of our wages, the disparity between the employees and Julie Sweet as a woman CEO is still plain to see.] Furthermore, if women attaining more lucrative/visible/prestigious careers such that they can readily disavow the liberatory struggle of the majority of women globally (not necessarily that they become the immediate oppressors of their own gender) is the goal, then is that not also unethical?

Now, does this mean I throw tomatoes when I see someone’s acceptance into an Ivy League (that would be some major cognitive dissonance on my end), or a LinkedIn announcement of someone receiving a job offer from a top consulting firm? Not quite. However, these achievements can never be the extent of “empowerment” if the end goal is a new world where everyone has equal opportunity to actualize their unique potential.

Premise II.III: Meritocracy (rugged individualism, social Darwinism’s every person for themselves, pulling yourself up by the bootstraps, poor people are lazy, billionaires earn their fortune with business savvy, etc.) takes on cultural iterations (Black excellence, model minority, women’s empowerment) that pits people against one another, siloes liberatory struggles, and hinders revolutionary-minded action.

Hi, kanto readers! The past 3 weeks have seen me in (a hopefully brief) transition. I’m taking care of myself as wholly as I can, and have been practicing reading-writing flows more than I had been able to at the beginning of this year. I wanted to end today’s post with Emory Douglas’s graphic art.

Douglas became the Revolutionary Artist and Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party (BPP) in 1967 until its dissolution in the 80s by the FBI, and he designed the front and back pages of the BPP’s newspaper (called “The Black Panther”). In looking for politically-agitating graphics, as I was initially trying to place the disturbed affect that came over me seeing reactions to Claudine Gay’s resignation, I came across some of Douglas’s works.

Subscribed

Fredric Jameson used this (now oft-quoted) phrase in his book The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic Act (1981), which I came to learn about through Barbara Foley’s book Marxist Literary Criticism Today (2019).

Once you click on the hyperlink, you can refer to “AP U.S. History Concept Outline,” or you can Google "AP United States History Course Framework” yourself, and the document that says “Effective Fall 2017” should be the first or second suggestion that populates. Both documents have the same wording for Concept 5.1.

Further reading: Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land (2018) by Leah Penniman, a book that this friend was reading recently to inform their agriculturally-based livelihood. When I think of “land is life,” this friend comes to mind.

Further reading: The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex (2017) by INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence, a key text that this friend told me shapes their thinking as a non-profit worker.

Further reading: Walang Hiya: Literature Taking Risks Toward Liberatory Practice (2010) edited by Lolan Buhain Sevilla and Roseli Ilano, one of the books that this friend lent me when I was working on my undergraduate English thesis.

Further reading: “Slavery, Race and Ideology in the United States of America” (1990) by Barbara J. Fields who explains why “race is not an idea but an ideology.” Note that the hyperlinked website is only an excerpt from the entire article.